Hong Kong, “The Key to the Lock of the World” Report

By Dr. Frank J. Collazo

December 28, 2007

Hong Kong and its Territories

Introduction to History:

Hong Kong and Kowloon

The city of Hong Kong, left,

faces Victoria Harbor on the northern part of Hong Kong Island. Kowloon, right,

is situated across the harbor on the mainland. Both are part of the Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China.

Yang Liu/Corbis

Hong Kong, administrative region of

China, consists of a mainland portion located on the country’s southeastern

coast and about 235 islands. Hong Kong is bordered on the north by Guangdong

Province and on the east, west, and south by the South China Sea. Hong Kong was

a British dependency from the 1840s until July 1, 1997, when it passed to

Chinese sovereignty as the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR).

British control of

Hong Kong began in 1842, when China was forced to cede Hong Kong Island to

Britain after the First Opium War. In 1984 Britain and China signed the

Sino-British Joint Declaration, which stipulated that Hong Kong return to

Chinese rule in 1997 as the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) of

China. The Joint Declaration and a Chinese law called the Basic Law, which

followed in 1990, provide for the SAR to operate with a high degree of economic

autonomy for 50 years beyond 1997.

The first permanent settlement

in what is today Hong Kong probably occurred about 2,000 years ago during the

Han dynasty (206 bc-ad 220). Little growth took place until

the 19th century, owing to China’s imperial policy of inward development, with

a focus away from developing the resources of coastal areas. Also, despite Hong

Kong’s proximity to the port city of Guangzhou, all foreign trade with China

was controlled through a small Chinese merchant guild in Guangzhou known as the

Co-Hong, and contact with foreigners was highly restricted.

The British, who wished

to expand their trading opportunities along China’s coast, became interested in

Hong Kong in the early 19th century. They also desired a location to serve as a

naval re-supply point, similar to the role Singapore was playing at the

southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. The trade of opium, a highly profitable

product for British merchants and eventually an illegal import into China, led

to the Opium Wars and Britain’s acquisition of Hong Kong. In 1839, the Chinese

Special Commissioner imprisoned some British merchants in Guangzhou and

confiscated opium warehouses. The merchants were released, but the British

foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, dispatched naval forces and war ensued. The

British had a superior naval force and won easily, occupying Hong Kong Island

in 1841.

One year later, China

and Britain signed the Treaty of Nanjing (Nanking) that ceded Hong Kong Island

and adjacent small islands in perpetuity to Britain. Treaty disputes and other

incidents led to the Second Opium War in 1856, also won by Britain. The

conflict ended with the ratification of the Treaty of Tianjin in 1860. Among

other provisions, this treaty ceded 10 sq km (4 sq mi) of the Kowloon Peninsula

to Britain, thereby allowing the British to establish firm control over the excellent

natural harbor between Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula. In 1898

China leased the New Territories to Britain for 99 years, adding more than 900

sq km (350 sq mi) of land and considerable territorial waters to Hong Kong.

Hong Kong grew slowly

during the 19th century, although gaining the New Territories added a

substantial rural population. By 1900 there were perhaps as many as 100,000

people. The territory began to grow more rapidly in the 20th century as

employment in Hong Kong’s developing light industries attracted Chinese

immigrants. Instability in China associated with the Republican Revolution of

1911 and World War I (1914-1918) also stimulated Chinese to move to Hong Kong.

This wave of population growth was halted during World War II (1939-1945) when

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Hong Kong for almost four years. After the

war Hong Kong had a population of about 600,000 people. A new wave of

population growth occurred when Chinese immigration resumed after World War II

and a growing civil war in China further prompted migrants to move to Hong

Kong. By 1947 the population had reached about 1.8 million.

Hong Kong’s greatest growth

and development occurred after the Communist takeover of China in 1949, when

the commercial and shipping functions of Guangzhou and Shanghai shifted to Hong

Kong. In addition, new industrial investments based on low-cost and productive

labor led to rapid expansion of industrial employment. Although, officially cut

off from easy ties with China during the early decades of the Communist regime,

trade and travel between Hong Kong and China in fact flourished. Hong Kong

served as China’s window to the world during the Chinese administration of Mao

Zedong. After Mao’s death in 1976, Hong Kong’s role as a banker to China, and

as its supplier of information, technology, and capital, intensified.

In the 1980s the impending

1997 expiration of Britain’s lease of the New Territories necessitated

negotiations between Britain and China. Britain agreed to return all of Hong

Kong to Chinese sovereignty at the end of the lease and the Sino-British Joint

Declaration was signed in 1984. Despite the change in Hong Kong’s political

status to a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China on July 1, 1997, the

territory has continued to strive to maintain its economic role and the

confidence of the world community in its banking, trading, and shipping.

Tung

Chee-hwa served as the Hong Kong SAR’s first chief executive from 1997 to 2005;

he resigned before the end of his second term in 2007, citing health reasons.

His deputy, Donald Tsang, took over as acting chief executive until a successor

could be determined. Tsang won nominations from 710 of the 800 election

committee members and was formally named chief executive in June 2005. Tsang

was appointed to serve out the remaining two years of Tung’s term, rather than

to a full five-year term.

First

Opium War

The breakup of the EEIC

monopoly was the immediate cause of the First Opium War, both because it led to

a huge increase in opium traffic and because, without the EEIC to serve as a

buffer, the British government now found itself obliged to intervene more

frequently in China. A vocal part of the English public clamored for greater

access to China’s huge market, and Britain often sought these goals through

bluster and the threat of force.

China saw the problem

differently and moved to stem the trade imbalance and the opium craze that

plagued its people. In late 1838 the Chinese appointed a famed official, Lin

Zexu, as imperial commissioner and sent him to Guangzhou to solve the problem.

In March 1839 Lin ordered the British merchants to hand over all of their opium

stocks within three days and to sign a bond pledging never again to traffic in

the drug under penalty of death. When British superintendent of trade Charles

Elliot attempted to negotiate, Lin suspended trade and held all foreign

merchants hostage. Elliot then ordered the merchants to hand over their opium

to him, after which he surrendered it to Lin. Lin washed some 9 million Mexican

silver dollars worth of opium into the sea, not realizing that English patriots

would view this as destruction of Crown property.

While Lin and the British

merchants jousted over the signing of the bonds, officials in England

dispatched an armed force to China. The Chinese had prepared for war at

Guangzhou, but the British force simply blockaded that city on its way north

toward the capital of Beijing, where officials met with the Chinese. The result

of subsequent negotiations was the Convention of Quanbi in January 1841, in

which the bare minimum of British demands were met. The agreement was

subsequently rejected by both sides: The emperor was enraged that his

representative had made real concessions, while the British felt that Elliot

had failed to press his advantage.

|

Sir Henry Pottinger replaced Elliot in August 1841 and

immediately directed his forces to occupy important cities along the coast,

including Ningbo and Tianjin. In the spring of 1842 the English renewed their

offensive, triumphing readily over valiant but under armed Chinese

resistance. By late June, the British occupied Zhenjiang, an important

communication center and entry to the Grand Canal, the artery by which rice

from the southern regions reached the northern capital. The Chinese agreed to

negotiate, and at gunpoint they signed the Treaty of Nanjing (Nanking) on

August 29, 1842. The treaty more than fulfilled England’s original goals: The

cohong was abolished, four more Chinese ports were opened to trade (Fuzhou,

Ningbo, Shanghai, and Xiamen), and the island of Hong Kong was ceded to the

British. The Second Opium War |

|

The Second Opium War was

in many ways an inevitable sequel to the first. The Chinese were not eager to

implement the terms of a treaty that they saw as unfair. Still, skillful

Chinese diplomacy and a number of other political distractions kept the

conflict from boiling over for a number of years. On the British side,

merchants were unhappy because they did not see a spectacular rise in profits

from the China trade after the First Opium War; they blamed their

disappointment on Chinese foot-dragging. In addition, the Treaty of Nanjing did

not address the opium issue. Opium smuggling continued, and this only increased

Chinese resentment of the foreigners.

The Arrow Incident of

1856 was the spark that ignited the Second Opium War. The Arrow was a

ship owned by a Chinese resident of Hong Kong, and it was registered with the

British there. On October 8, 1856, Chinese officers searching for a notorious

pirate boarded the ship—without British permission—while it was docked off

Guangzhou, hauling down the British flag as they did so. This minor incident

quickly escalated into a shooting war.

The British sent an expedition

to seek redress and were joined by a French task force. (A French missionary

had been murdered in inland China in February 1856.) After some delay, the

joint force took Guangzhou in December 1857 and then moved north to threaten

the capital once again. By June 1858 the superior power of the Europeans and

their refusal to compromise culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Tianjin,

the most important term of which was the right of foreigners to establish

permanent diplomatic residence in China’s capital. The treaty also opened ten

new ports to foreign trade.

When the foreigners returned

to ratify the treaty the following summer, however, angry Chinese forces opened

fire, killing more than 400 British men and sinking four ships.

A

much larger Anglo-French force returned a year later, in August 1860, and

invaded the Chinese capital, sending the imperial court into flight and burning

the Summer Palace. On October 24, 1860, British leaders forced the Convention

of Beijing on the defeated Chinese, establishing once and for all the right of

foreign diplomatic representation in China’s capital. Many restrictions on

foreign travel within China were removed, and missionaries received the right

to work and even own property in China. The opium trade, the catalyst for the

whole dispute, was legalized.

|

|

|

Significance |

|

The Opium Wars are extremely

important to China’s modern history. The wars, and the unequal treaties forced

on the Chinese by the West, compromised China’s sovereignty and weakened the

country’s political institutions during a crucial period in its history. The

events contributed to the collapse of the Qing dynasty—the country’s last

imperial dynasty—in the early years of the 20th century. Although some

historians have argued that the conflicts constituted a painful but much needed

jolt to shake China out of time-bound traditions, the Chinese look back on the

Opium Wars as a cruel and greedy exercise in “might makes right.”

Hong

Kong Transition

The 6

million British colonial citizens of Hong Kong, a moment of truth—arguably the

most important that they have ever had to confront—was to arrive at midnight on

June 30, 1997. On that day their prosperous territory, which has been under the

generally benign governance of the faraway British parliament since 1842, was

to change hands.

Under the

terms of a solemn treaty signed nearly a century ago, the territory was to pass

into the control of the country from which many of the present inhabitants fled

as refugees from the People's Republic of China. The British territory was to

become, in other words, Chinese. The bastion of capitalism was to fall, under

the authority of Communists. Six million people, whether they liked it or not,

were to watch their nationalities and their citizenships and their futures

change in the blink of an eye.

From China's

perspective, the event was a satisfactory end to more than a century of

humiliation in which a foreign power—Great Britain—had illegal control of a

significant bit of its land. China regarded that land as inalienably Chinese

territory. From the perspective of Britain, which has seen its empire shrink,

territory by territory, for the best part of the last 50 years, the

handing-over of Hong Kong was something to be regretted, although it was not

unexpected.

During the

last century and a half, Hong Kong has languished and prospered under a

significant degree of personal liberty. There has been a fair and just legal

system, a properly regulated commercial system, and some semblance of

democracy. And under this arrangement most residents of Hong Kong have managed

to achieve a standard of living and education utterly unknown in China. For

example, in 1990 the literacy rate in Hong Kong was virtually 100 percent; in

China, some 182 million people out of an estimated population of about 1.2

billion could not read or write.

The British colonial period was partly responsible for the many freedoms that existed in Hong Kong—freedom of the press, of religion, of association, of speech—its coming end was a cause for grave concern.

1989 Tinnanmen Square Massacre Impact on Hong Kong

Few in Hong

Kong can forget, for instance, the tragedy of the 1989 Tinnamen Square massacre

in Beijing, the capital of China, when China's People's Liberation Army crushed

a prodemocracy rally. Hundreds of demonstrators were killed. Most in Hong Kong

know how harshly China is accustomed to dealing with those who stand up against

Communist authority. Most are aware of the alarmingly high degree of

corruption—both official and unofficial—within the People's Republic.

Different Societies

It will be a

challenge for Hong Kong and China—two societies that have evolved over the last

150 years into entities that are dramatically different from each other—to

unite and create a blend of the two ways of life. The future, for so fragile a

place as tiny Hong Kong, is uncertain indeed. The handover had been anticipated

for a long time—anticipated, but until lately, rarely spoken about.

The Tea Connection

The link

between the innocent cup of tea, and today's alarm over the future of Hong

Kong, goes like this: The first tea

imported into Britain came from China via the Portuguese, who had a trading

post in their colony of Macao on the southeastern coast of China.

In the 1680s

ships brought sacks of the dried leaves up from Lisbon, the capital of

Portugal, to the port of London, where they were sold at a tiny and fashionable

café called Garway's Coffee House. It was an instant hit: Londoners fell upon

the new drink with unbridled enthusiasm.

Before the

demand was so huge, it was decided that Britain should import the tea itself,

rather than let the Portuguese act as the middlemen. The only entity then

capable of doing business with the Chinese was the East India Company, based in

the eastern Indian city of Calcutta, which promptly sent ships to the Chinese

port of Guangzhou (Canton) and asked to buy some tea.

The Chinese

merchants were happy to oblige—but they would only accept metal in payment for

it: gold, silver, or copper bars. They did not want any of what they considered

the worthless paper bills that were customarily offered by Westerners in

payment. The British agreed, and a healthy trade began.

The

financial arrangement then ran for many years—until the time came when the

demand for tea back in England was so huge that the East India Company ran out

of metal with which to pay.

Late into the first half of the 19th century, however, the Chinese began to balk at the arrangement. The emperor in Beijing objected at the notion of “foreign mud” being imported and causing addiction among his subjects. He ordered action from his viceroy in Guangzhou, where the Indian opium was being imported—largely through a firm of Scottish grocer-traders, the Jardines and the Mathesons. After some hesitation the local authorities did indeed act, confiscating hundreds of boxes of the drug and, as today, burning them.

The British

traders were enraged, and looked to their faraway government for help, which

came in the shape of a squadron of fast ships, dispatched to China for the

purpose of insisting on Britain's rights to free trade. The first of the

so-called Opium Wars was joined, and the Chinese, militarily backward after

centuries of self-imposed isolation, lost. The British were in a position to

exact retribution and as was common in Britain's imperial heyday, they decided

that, in addition to shiploads of silver bullion and a treaty promising

respect, they would get what they liked best of all—land.

Specifically,

under the terms of the famous 1842 Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing), they wanted

sovereign control over the island of Hong Kong. A disappointed London

politician described the island as “a barren rock, with hardly a house on it.”

But barren or not, it was ceded in perpetuity: It became the newest part of the

fast-expanding British Empire. Winston Churchill, Great Britain's prime

minister in the 1940s and 1950s, later described Hong Kong as “the key to the

lock of the world.”

Treaty of Nanjing, August 29, 1842

The Treaty

of Nanking was the first of three treaties between Britain and China.

Brought to the negotiating table by the Opium War, China agrees to open up more ports to foreign trade, ends the tributary system, yields Hong Kong to Britain, and agrees to pay war damages. An unequal treaty, China gets nothing in return, although opium remains illegal.

Treaty of

Tientsin (Tianjin)

The second,

the Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin), forced on the Chinese in 1861 after they had

taken a further drubbing at the hand of British forces, gave Britain control of

a section of the Chinese mainland just across from Hong Kong island, and known

as Kowloon (Nine Hills).

Japanese Conquests in Asia

Under the

circumstances it was inevitable that the British should intensify the

fortification of Hong Kong, which became legitimate on the expiration of the

Washington Naval Treaty at the end of 1936. A $25,000,000 defense program has

been enlarged and rushed toward completion. Artillery and machine-gun

emplacements have been strengthened and concealed hangars built, while

civilians have been recruited for volunteer military and first aid work which

will supplement that of the regular forces. Military roads, trenches and

concealed munitions dumps have been constructed; a new anti-aircraft defense

system evolved; and a force of six battalions of troops and 300 first-line

planes established in the territory.

Yet despite

these measures, Hong Kong is no longer considered an important strategic

outpost of the Empire. In case of a world war in which Britain and Japan were

involved, it is generally agreed that the imperial defense line would be

withdrawn to Singapore, and that Hong Kong's military importance would be

limited to delaying action against an enemy advance. Hence the future of the

colony, which contains nearly $100,000,000 in British investments, is far from

secure. Even without a war, these investments would be ruined if the Japanese

were permanently to cut off Hong Kong's intercourse with the Chinese

hinterland.

Despite a

previous warning from both the French and British that any attempt to occupy

the Island of Hainan would lead to undesirable consequences, the Japanese on

Feb. 9, pleading military necessity, seized this island. Hainan lies directly

athwart the line between Singapore and Hong Kong, not far from the French naval

base at Cam Ranh in French Indo-China. The Japanese had bombed the island in

September 1938, and following protests from the French Government declared it

would be secure from further attack provided France would allow no military

supplies destined for China to move through Indo-China. The French agreed. The

occupation of Hainan opens the way for a direct thrust at Indo-China itself,

and for this reason has been a source of anxiety to the French Government.

Trade with

Canton naturally dropped rapidly after that city fell to Japan, for the

invaders soon won complete control over rail and river communications between

the two cities. But since the fall of Shanghai, Hong Kong had become China's

principal entry port, and the traffic continued by other routes. Coastal

steamers carried cargo to and from the treaty ports of Swatow, Amoy and

Foochow, the Portuguese colony of Macao, and French Kwangchowan. The great

China tea market was transferred from Shanghai to Hong Kong. Because of these

developments, Hong Kong's exports of merchandise were as high in the first six

months of 1939 as in the same period of the record year 1938, while its imports

declined by only 12 per cent.

The life of

this small but important British colony was dominated during 1940 by two wars —

one in Europe and one in Asia — which tended to converge into a single great

struggle as the bonds between Japan and the Axis were drawn closer.

Approximately 1,000,000 Chinese refugees continued to subsist in the territory,

a few living on the riches they had brought with them and the rest relying on

public and private charities. Their presence intensified the potential

difficulties of importing adequate foodstuffs and raw materials and finding

markets for the colony's exports.

These

problems, not serious in normal times, became more pressing as Japanese troops

moved southward in increasing numbers. In 1939 the invading forces had occupied

all the Chinese territory paralleling the Hong Kong land border; in 1940 they

penetrated into Indo-China under agreement with representatives of the French

government at Vichy. More and more completely Hong Kong assumed the aspect of

an isolated outpost of empire, subject to blockade by land and sea and, in the

long run, indefensible.

In the vast

area of land and ocean they had marked for conquest, the Japanese seemed to be

everywhere at once. Before the end of December, 1940, they took British Hong

Kong and the Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati) and Guam and Wake Island (U.S.

possessions), and they had invaded British Burma, Malaya, Borneo, and the

American-held Philippines. British Singapore, long regarded as one of the

world’s strongest fortresses, fell to them in February 1942, and in March they

occupied the Netherlands East Indies and landed on New Guinea. The American and

Philippine forces surrendered at Bataan on April 9, and resistance in the

Philippines ended with the surrender of Corregidor on May 6.

Thailand Support Japan in WWII

In 1940 Thailand fought

a brief war with French Indochina, which had become cut off from France as a

result of World War II. With Japanese mediation, the Thai government regained

the territories in Laos and Cambodia that had been ceded to France in 1904 and

1907. On December 8, 1941, Japanese troops landed on Thailand’s southern coast.

This was around the same time that the Japanese launched attacks on Pearl

Harbor, Midway, Guam, Manila, Hong Kong, and other sites.

After tense meetings

with the Japanese and his cabinet, Phibun agreed to allow the Japanese to move

their troops through Thailand to invade and occupy the British-controlled Malay

Peninsula, Singapore, and Burma. In January 1942, Thailand declared war against

Britain and the United States. In 1943, Japan rewarded the Phibun government

for its cooperation with the Japanese by awarding Thailand part of the

territory that had been incorporated into British Burma in 1885 and the four

Malay states that Siam had been forced to cede in 1909.

Hong

Kong Flu

Scientists succeeded in

reconstructing the 1918 influenza virus in 2005 after finding samples of the

virus in the preserved tissues of three people killed by the Spanish flu. The

scientists concluded that it was an avian flu virus that spread directly to

humans. The virus penetrated deep into human lung tissue, causing a type of

pneumonia that was capable of killing the young and healthy.

In 1957, a flu outbreak

occurred in Guizhou, a province in southwestern China. Within six months, most

areas of the world were battling what became known as Asian flu. Before the

1957-1958 pandemic subsided, an estimated 10 to 35 percent of the world’s

population had been affected. The overall mortality rate, however, was

comparatively low.

|

About a

decade later, a variant of the virus that caused the 1957-1958 pandemic originated in either

Guizhou or Yunnan province in southern China. The variant was first isolated and

identified in Hong Kong in July 1968. Within a few months, cases of this Hong

Kong flu appeared around the world. Hardest hit by the pandemic were children

under age 5 and adults aged 45 to 64. In the United States, an estimated 30

million people were infected and there were some 33,000 influenza-related

deaths. Land

and Resources

|

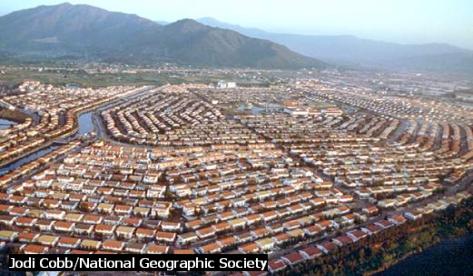

New Territories, Hong Kong

In 1898 Britain leased from China a

large area of agricultural land and surrounding waters and added it to Hong

Kong. The British named the region the New Territories and developed the area

into numerous new towns. In 1984 Britain agreed to return the New Territories and

the rest of Hong Kong to China upon the expiration of the lease in 1997.

Jodi Cobb/National Geographic

Society

Geography

The total land area of

Hong Kong is small, comprising only 1,092 sq km (422 sq mi), about two-thirds

the size of Long Island, New York. The surrounding territorial waters cover

1,830 sq km (707 sq mi). Hong Kong’s mainland portion consists of the urban

area of Kowloon and a portion of the New Territories, a large area that became

part of Hong Kong in 1898. Lantau Island (also called Tai Yue Island), ceded to

Hong Kong as part of the New Territories but often considered separate from

that region, is the largest island. Located about 10 km (6 mi) east of Lantau

Island and across Victoria Harbor from Kowloon is Hong Kong Island. The city of

Hong Kong (also known as Victoria) faces the harbor on the northern part of the

island. The city is the site of the SAR government offices and the chief

business district, known as Central.

Topography

Despite the small size

of the Hong Kong SAR, the topography is varied and rugged because it is largely

folded mountains. There are more than 20 peaks over 500 m (1,640 ft), and the

tallest, Tai Mo Shan in the New Territories, rises to 957 m (3,140 ft). Hong

Kong’s greatest asset is its deep and well-protected harbor between Hong Kong

Island and Kowloon. Level land for development is scarce. Less than 15 percent

of the land is developed because of the rugged terrain. Land reclamation

schemes began in the mid-19th century and they continue to be important means

of acquiring new land for urban development. Examples of reclaimed land include

stretches of coastline on either side of Victoria Harbor.

The only significant river

is the Sham Chun, a small river that forms the northern border with Guangdong;

all other drainage is small streams. The lack of sufficient drinking water is a

serious problem; more than 80 percent of Hong Kong’s potable water comes from

Guangdong.

Busy Aberdeen

A sampan makes its way through

Aberdeen harbor on the southwest coast of Hong Kong Island. A haven for pirates

two centuries ago, Aberdeen gradually evolved into a fishing community that

continues to attract people to its floating restaurants. Today, it is home to

thousands of boat dwellers.

Porterfield-Chickering/Photo

Researchers, Inc.

Climate

Hong Kong’s climate is

subtropical and monsoonal. The average daily temperature range is 26° to 31°C

(78° to 87°F) in July and 13° to 17°C (55° to 63ºF) in February. Rainfall

averages 2,159 mm (85 in) a year. Summers, which last from May to September,

are long, hot, and humid. Typhoons regularly cross Hong Kong in summer and

autumn. These powerful storms bring violent winds and extremely heavy rains

that occasionally cause flooding and landslides. The winter, lasting from

December to March, is cool and drier.

Rain

Fall

The heavy rainfall washes

away many nutrients from the soil, making it generally thin, poor, and unsuitable

for intensive agriculture. Moreover, there is little available land for farm

cultivation. Most of the original forest vegetation was long ago cut or burned

and replaced with grasses or planted tree species such as pine and eucalyptus.

Wooded hills now account for about one-fifth of the land area, whereas

grasslands, badlands, and swamps make up more than one-half.

Bird

Species

Hong Kong, in association

with the World Wide Fund for Nature, maintains an important marsh reserve for

birds, Mai Po, along Hau Hoi Bay (also called Deep Bay) and the river boundary

with Guangdong. Mai Po attracts about 260 bird species, among them numerous

ducks, wading birds, kingfishers, warblers, and marsh harriers. The reserve is

an important stopping point for migratory birds flying between Siberia and

tropical Southeast Asia and Australia. In addition to birds, Hong Kong has

numerous small mammals and reptiles.

|

The People of Hong Kong |

Street Scene, Hong Kong

Much of Hong Kong’s population is

concentrated on Hong Kong Island and across Victoria Harbor in Kowloon.

Population densities there reach as high as 40,000 people per sq km (100,000

per sq mi), among the highest in the world.

Ron Giling/Panos Pictures

Population Density

At the time of the 1991 census, Hong Kong had a population of

5,674,114. The 2006 population was 6,940,432, indicating a population density

of 7,018 persons per sq km (18,176 per sq mi). The population is unevenly

distributed, however, with the greatest concentrations of people in Kowloon and

across the harbor on Hong Kong Island. Some districts, such as Mong Kok in

Kowloon, have population densities of about 40,000 persons per sq km (about

100,000 per sq mi), among the highest urban densities in the world. Although

birth and death rates are comparatively low in Hong Kong, migration from other

parts of China creates a high population growth rate, and migrants now make up

about 40 percent of the population.

Ethnic

Groups

About 98 percent of the

people are ethnic Han Chinese. Of these, 90 percent speak the Cantonese dialect

of Chinese and come from southern China, or are descendants of people who

originated there. The remaining 10 percent of Han Chinese come from other

regions of China and speak other Chinese dialects. About 2 percent of the total

population comes from or have ancestors who came from foreign countries, most

from Southeast Asia. Many people practice ancestral worship, owing to the

influence of Confucianism, but all major religions are represented. Chinese and

English are Hong Kong’s official languages.

From 1984 to 1997, due

to the uncertainty of the transition back to China, thousands of well-educated

and wealthy Hong Kong citizens moved to countries such as Australia, Canada,

and the United States, where they obtained permanent residency status or

citizenship. However, many returned to Hong Kong after their initial

emigration.

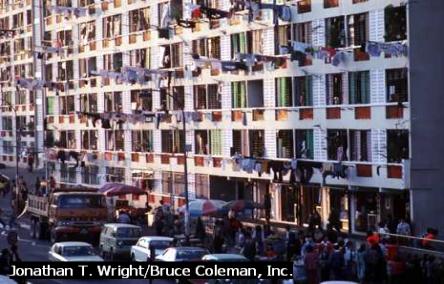

Hong Kong Housing

Densely packed high-rise apartments in

Hong Kong demonstrate population pressures that shape the city and other urban

centers, especially in the developing world. Large numbers of people from rural

backgrounds, many from mainland China, come to Hong Kong seeking work.

Jonathan T. Wright/Bruce Coleman,

Inc.

Urban Reconstruction

In 1973 the Hong Kong

government began a massive program of housing construction and industrial

relocation in the New Territories. The program is an attempt to lessen the

crowding of Kowloon and the Central district of Hong Kong Island, and to reduce

the demand for transportation by building planned communities near employment

centers. Since many people in Hong Kong prefer living near their workplace,

this approach has helped to accommodate Hong Kong’s large population on its

small area of land.

Chinese New Year in Hong Kong

Parade participants wear costumes in the

form of mythical creatures as part of the Chinese New Year Parade in Hong Kong.

The Chinese New Year is also known as the Spring Festival and takes place

between January 21 and February 19, depending on the lunar calendar.

Celebrations begin with several days of cleaning to show the kitchen god

special respect. Popular communal events include the dragon and lion dances,

which take place in the street.

Kevin Fleming/Corbis

Education System

Education is free and

compulsory for all children from the age of 6 to 15, and adult literacy is over

90 percent. Only a small percentage of high school graduates attend college or

university on a full-time basis, however. There are seven colleges and

universities, including two polytechnic schools. The largest and oldest

institution of higher learning is the University of Hong Kong, founded in 1911.

The Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts offers courses in dance, music,

theater, and technical arts. There are also more than a dozen technical

institutes, technical colleges, and teacher-training colleges, which have large

numbers of part-time students.

Dragon Boat Festival

To the cheers of spectators crowding

the harbor, competing boats with as many as 50 paddlers each skim the water

during the Dragon Boat Festival races, held each June. The races commemorate

the heroic suicide of Qu Yuan, a respected 3rd-century-bc scholar who threw himself into a river when his earlier

predictions of political disaster—ignored by the emperor—came true. The races

emulate the actions of the inhabitants of Qu's village, who rowed their boats

out onto the river upon hearing of his tragic death.

Alain Evrard/Photo Researchers, Inc.

Cultural Attractions

Hong Kong has a variety

of cultural attractions and activities. The Hong Kong Arts Festival and the

Hong Kong International Film Festival are annual events. Professional music

companies include the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, the Hong Kong Chinese

Orchestra, and the Hong Kong Dance Company. The territory has a thriving film

and television industry. One of Hong Kong’s most popular actors is Jackie Chan,

who is known for his starring roles and stunts in action movies. Hong Kong

Disneyland opened in September 2005.

Customs of Hong Kong, Marriage and Family

Men and

women choose their own spouses. Couples tend to marry later (in their mid- to

late 20s) than in many countries. A large banquet is the highlight of the

elaborate wedding celebration. The banquet is often held after an afternoon of

"mah-jongg", a tile game that is a cross between dominoes and cards.

Chinese

family members are bound by a strong tradition of loyalty, obedience, and

respect. Hong Kong has one of the lowest divorce rates in the world. While

families have traditionally been large, a trend toward smaller families is

clear. Chinese do not usually display affection in public, but this is changing

among the younger generation. A source of stress for many families in

Hong Kong is the sharp difference between traditional values and modern

practices. The decision of many to leave Hong Kong before China took control in

summer 1997 also strained the traditionally strong family.

Eating

Rice is the

staple food. Chinese dishes are often prepared with pork, chicken, and

vegetables, but seafood is the most common ingredient in Hong Kong cooking. A

large variety of fruit is also available. Business is often conducted during

lunch or dinner. Lavish restaurant meals are traditional for weddings and other

special events.

The Chinese

use chopsticks for eating most meals, and visitors should always try to use

them when being entertained in a Chinese home or restaurant. Dishes of food are

placed in the center of the table, and the diners serve themselves by taking

portions of food with chopsticks and placing the food in their individual bowls

of rice. It is proper to hold the rice bowl close to the mouth when eating. A

host will refill a guest’s bowl until the guest politely refuses. Although

Chinese restaurants are in the majority, many different types of cuisine are

available in Hong Kong, including French, Mexican, German, Italian, and

Japanese. American, Thai, and Vietnamese styles of food are also popular.

Socializing

A handshake

is a fairly usual form of greeting. In Chinese, the surname comes first in a

name of two or three words, unless a person is addressing one of the many Hong

Kong Chinese who have Westernized their names.

On most occasions when a gift would be appropriate (such as weddings, festivals, and the Chinese New Year), the usual gift is money in a red envelope. At the Chinese New Year, single people receive envelopes of money from their families, and it is traditional for a guest to bring a gift of fruit or candy for the host. People offer and receive all gifts with both hands. It is important to show respect for one’s hosts and their home; this is done not only through good manners, but also by maintaining good posture. It is always polite to compliment one’s hosts, who are likely to say that they are not worthy of the praise. As in many countries in the region, age is revered and older people should be treated with particular respect.

Recreation

Films and television are perhaps the most popular forms of entertainment. Favorite sports include soccer, swimming, table tennis, skating, squash, tennis, basketball, and boating. Major spectator events include the Seven-a-Side Rugby Invitation Sevens, the Open Golf Championship, and the Super Tennis Classic. Hong Kong’s passion, however, is horse racing, the only legal form of gambling. Races are organized by the Royal Hong Kong Jockey Club and held at Sha Tin in the New Territories and in Happy Valley on Hong Kong Island between September and May.

Holidays and Celebrations

Chinese holidays are based on the lunar calendar and thus fall on different days of the Gregorian calendar each year. Although the International New Year is observed on 1 January, the celebrations for the lunar, or Chinese, New Year in late January or early February are far more exuberant. There are many beliefs and traditions associated with this holiday, which lasts around two weeks, although most people go back to work after three or four days of revelry. Some of the most widespread practices include making offerings to household gods, cleaning house, wearing new clothes, settling personal debts, and feasting at large banquets. The color red and loud noise are two hallmarks of this celebration: Both are said to drive off devils and wild beasts. Another custom is to write messages of prosperity and longevity on red paper and display them on doorways. It is a tradition in Hong Kong to go to flower markets after a New Year’s Eve feast.

Sometime in

March or April, the birthday of Kuan Yin, the Buddhist deity of mercy, is

celebrated. The holiday is observed mainly by women, who may make pilgrimages

to Kuan Yin’s temple to pray and leave offerings of fruit, flowers, and cakes.

The Ching Ming Festival in April is a time for honoring the dead.

The Tin Hau

festival in May is a birthday celebration of Tin Hau, the Queen of Heaven and

Goddess of the Sea. She is one of the most popular deities in Hong Kong and is

said to protect against shipwrecks, sickness, and rough seas. Festivities on

this day include parades, Chinese opera performances, and visits to Tin Hau’s

temples on brightly colored vessels. In June the Dragon Boat Festival is

celebrated with dragon boat races. Liberation Day is celebrated in August. The

Mid-Autumn Festival is a harvest holiday celebrated with lanterns and moon

cakes. On Chung Yeung in October, people tend the gravestones of family and

friends, make offerings of food, and fly kites. In Hong Kong, it is believed

that kites carry misfortune away into the skies.

Since the transfer of power in 1997, Hong Kong residents have

celebrated two more holidays: Reunification Day in July and National Day in

October. Christian holidays celebrated include Easter and Christmas Day (25

December). The day after Christmas, Boxing Day, is also observed.

Lifestyle

![]() Hong Kong’s prosperous

economy is reflected in the lifestyle of its people. They have one of the

highest standards of living in all of Asia, and it is more than 30 times higher

than China’s average standard of living. In 2004 Hong Kong’s per capita gross

domestic product (GDP) was $23,680, although much of the wealth is concentrated

into relatively few hands.

Hong Kong’s prosperous

economy is reflected in the lifestyle of its people. They have one of the

highest standards of living in all of Asia, and it is more than 30 times higher

than China’s average standard of living. In 2004 Hong Kong’s per capita gross

domestic product (GDP) was $23,680, although much of the wealth is concentrated

into relatively few hands.

Economy

|

Hong Kong's Busy Streets

Bright signs and busy shops line

Tsim Sha Tsui, a famous commercial district in Hong Kong. Located on the

southern tip of the Kowloon Peninsula north of Hong Kong Island, Tsim Sha Tsui

serves as Hong Kong's shopping and entertainment center, and features many

hotels, bars, and shops. It is the terminal for the Star Ferry, which for a

century provided the only public transportation to Hong Kong Island.

Will and Deni McIntyre/Photo Researchers,

Inc.

Economic Development

Trade with Canton naturally dropped

rapidly after that city fell to Japan, for the invaders soon won complete

control over rail and river communications between the two cities. But since

the fall of Shanghai, Hong Kong had become China's principal entrepôt, and the

traffic continued by other routes. Coastal steamers carried cargo to and from

the treaty ports of Swatow, Amoy and Foochow, the Portuguese colony of Macao,

and French Kwangchowan. The great China tea market was transferred from

Shanghai to Hong Kong. Because of these developments, Hong Kong's exports of

merchandise were as high in the first six months of 1939 as in the same period

of the record year 1938, while its imports declined by only 12 per cent.

Textile

Industry Crisis

The six

big-volume nations agreed to: a twelve-month ceiling on exports to become

effective Oct. 1, 1961, at the level of the twelve-month period which ended on

June 30, 1961; a special study to develop a long-term plan to be reported Apr.

30, 1962; a relaxation of import restrictions by nations that now impose

them—mainly in Western Europe. The principal import increases fell to France

and Italy; Japan received a slight increase. In a separate negotiation, Hong

Kong was asked to accept a 30 to 35 per cent cut.

There were

several clouds on the economic horizon for the colony. Its textile industry,

which now provides close to 55 per cent of value of direct exports, was

confronted with demands from the United States and the United Kingdom that it continue

to impose voluntary quotas. The 'big three' of the textile industry

associations, the Hong Kong Cotton Spinners' Association, The Federation of

Hong Kong Cotton Weavers, and The Hong Kong Cotton Weaving Mills Association,

continued through the summer to reject the idea of the quotas being extended

beyond January 1962, but finally agreed to an eleven-month extension. The Hong

Kong textile and garment industry was largely responsible for the growth of

Tsuen Wan, a new industrial and commercial center within the colony's

398-square-mile area. Over half of the 570,000 spindles are in Tsuen Wan.

1969

Economic Crisis

Damage to

the economy last year was not so bad as pessimists had feared. Foreign trade

expanded by 9 percent, tourist arrivals were 4 percent higher, and although

some money left Hong Kong this did not establish a trend. Sterling devaluation

at the end of 1967 caused a flutter and a loss in London-held reserves. The

Hong Kong dollar was also devalued, but by the smaller margin of about 7 percent.

In June the British Treasury negotiated a new form of reserve asset that would

protect the colony to some extent against the risk of further sterling

devaluation—part of Hong Kong's reserves could be held in British bonds

denominated in Hong Kong dollars. But there was some doubt in the colony as to

the real value of this concession, and it was overtaken in the autumn by the

Basel Agreement, under which all parts of the sterling area could gain

protection, which was, if anything, better.

Harbor

Tunnel between Victoria and Kowloon

In September

work began on the long-discussed cross-harbor tunnel between Victoria and

Kowloon. A British consortium of engineering firms was awarded the contract

after a long delay in obtaining the necessary guarantees for the financial

credit. Because the amortization for the tunnel would stretch into the period

immediately preceding the end of the colony's 99-year lease from China in 1997,

the problems of financing were obviously severe, and overcoming them

consequently boosted the morale of the colony's business community.

Moreover,

some residents of Hong Kong felt that the commissioning of the project would

deter Peking from taking any drastic action against the colony pending its

completion, because the tunnel will clearly add greatly to the value of the

area. There is no bridge across the harbor, and traffic has hitherto had to

rely on ferries. The next large-scale project will be the extension of the

runway at Kai Tak Airport for the jumbo jets, a $15 million scheme for which

the financing was also a problem

Water Shortage

During early

1964 the water shortage was so acute that residents could get water only every

other day and then for only a few hours. Communist China, however, signed a new

agreement to provide additional fresh water for the colony; and seven typhoons

left the reservoirs full. For the first time in many years this British crown

colony had no water shortage during 1965, as the agreement to buy water from

the Chinese mainland seemed to work smoothly. However, three major crises kept

the colony buzzing. The first was a run on the banks in the beginning of the

year. Financial experts were at a loss to explain it, but the government was

forced to impose restrictions on withdrawals that were not lifted until

February 15.

Strategic Location

Hong Kong’s position as one of the world’s most

important economic centers

is based on several factors. It is located midway between Japan and Singapore,

and it lies astride the main shipping and air routes of the western Pacific. It

also has long served as a major port of entry and trade for China, which uses

Hong Kong as a primary link to the world economy.

Trade

Furthermore,

Hong Kong has a favorable atmosphere for business and trade. Despite the

uncertainty associated with its return to China, which has a Communist

government, Hong Kong continues to thrive economically and attract new

migrants. Hong Kong’s economy has always been based upon commerce, trade, and

shipping, and today it vies with Singapore as the world’s largest container

port. Industry and tourism are also important, and agriculture continues to

provide a significant share of the territory’s food and flower supplies,

although Hong Kong must import the majority of its food.

Benefits of Free Trade

The last

three decades have seen a significant improvement in living standards for

hundreds of millions of people. Without exception, the countries in which

living standards have improved most rapidly have substantially reduced trade

barriers and increased their exports. Since 1970 Asia’s “four little

tigers”—Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore—have been transformed

from impoverished areas into some of the world’s richest areas. Many of their

citizens now enjoy living standards comparable to those of the United States

and Europe. Not coincidentally, these four entities are among the 20 largest

traders in the world.

Agriculture

Farming is a declining

sector, because of the shortage of suitable farmland. There are now less than

2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) under cultivation for vegetables and flowers,

although these produce about one-quarter of the fresh vegetables consumed.

Increasingly, farmers are growing premium food and flower varieties, which

fetch higher market prices than the traditional rice crop. Pig farming is also

important. Hong Kong’s fishing fleet is significant and contributes about

two-thirds of the live and fresh marine fish consumed each year.

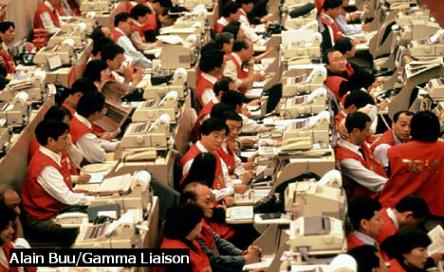

Stock

Market

Hong Kong Stock Traders

Hundreds of traders keep close watch

on their computer screens in one of Hong Kong's several stock exchanges. As a

chief financial center, Hong Kong also serves as a vital intermediary on investment

and foreign exchange between mainland China and the rest of the world.

Alain Buu/Gamma Liaison

Industrial Development

Manufacturing developed

rapidly in the 1950s and grew to become the most important economic sector in

the early 1980s, when manufacturing employment reached nearly 905,000. Hong

Kong was a leading producer of textiles, plastics, rattan furniture, watches,

and clocks. Manufacturing thereafter declined rapidly, however, as the economy

of Hong Kong underwent major structural change. Manufacturers began shifting

the location of their production facilities to neighboring Guangdong Province

and other locations in China, where labor and land costs were much lower.

By

the early 1990s industrial employment had declined to less than 575,000, and by

2005 it was about 185,000. However, the relocation of labor-intensive

manufacturing to mainland China has been partially offset by the fact that many

of the relocated businesses have continued to conduct export operations in Hong

Kong. In addition, Hong Kong now manufactures goods that require a more highly

educated and skilled labor force, such as electrical and electronic products.

Most importantly, the services sector has experienced rapid growth, especially

in finance, insurance, real estate, and business services, giving Hong Kong the

sophistication of a metropolitan economy.

Hong Kong is among the

leading trading centers in the world, and shipping and trade continue to be

important aspects of its economy. The market is generally open and favorable to

trade, and Hong Kong has been successful at balancing its imports and exports.

Many of its exports are actually re-exports, products that are manufactured in

other parts of China or other countries but distributed through Hong Kong.

These products include clothing, textiles, telecommunications and recording

equipment, electrical machinery and appliances, and footwear. Imports consist

largely of consumer goods, raw materials, transportation equipment, and

foodstuffs. Extensive trade occurs with other regions of China. In addition,

Hong Kong’s leading international trading partners are the United States and

Japan.

Fishing in Hong Kong

Fishing in Hong Kong

Fishing is an important source of

income and trade for Hong Kong. Due to an extreme land shortage, the government

must import most of its food supply. The residents in this photo are fishing in

Aberdeen Bay near Hong Kong.

Benjamin Rondel/The Stock Market

Currency, Floating Hong Kong Dollar

The Hong

Kong dollar was allowed to float at the end of 1974, after having been pegged

to the U.S. dollar for the preceding 21 months. At about the same time, the

so-called 'Basel agreement,' by which Hong Kong kept a proportion of its

reserves in sterling in return for partial British guarantees against

devaluation losses, was terminated by British Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis

Healey.

The unit of currency is

the Hong Kong dollar (7.79 Hong Kong dollars equal U.S.$1; 2004 ). The

Hong Kong Monetary Authority performs the functions of a central bank and

authorizes three commercial banks—the Bank of China, HSBC (formerly the Hong

Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation), and the Standard Chartered Bank—to

issue Hong Kong dollars. The terms of the Sino-British Joint Declaration of

1984 allow Hong Kong to continue issuing its own currency until the year 2047.

Tourism

Tourism is one of Hong

Kong’s most important service activities and it is the third largest source of

foreign exchange earnings. Tourism dollars injected more than $7 billion into

the Hong Kong economy each year of the early 1990s, when nearly 9 million

tourists visited annually. In 2004, 13.7 million tourists visited Hong Kong.

Most visitors came from Taiwan, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, and other locations

in East and Southeast Asia. Many European and North American tourists also

visited.

Contract

Bridge

Travel-with-Goren

Company hosted two trips to the Orient, in which bridge stalwarts visited such

Far Eastern cities as Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Bangkok, and one to the Caribbean.

Tournament bridge provided the main source of entertainment as the luxury

liners steamed to their various ports of call. The trips to the Orient were a

combined air and naval operation as the tourists cruised to the Far East aboard

the U.S.S. Roosevelt and returned by jet.

Seaports/Airports

In addition to its excellent

deepwater port and extensive maritime connections, Hong Kong has one of Asia’s

main airports, the Hong Kong International Airport. Located on the islet of

Chek Lap Kok off Lantau Island, the airport opened in 1998, replacing the old

Kai Tak International Airport. There is passenger and freight rail service to

Guangzhou.

Highways

Hong Kong has an extensive

network of roads in the New Territories, in Kowloon, and on Hong Kong Island.

This network is supplemented by the Mass Transit Railway (MTR), which connects

Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, and the New Territories. A 33-km (21-mi) electric

trolley line operates on Hong Kong Island, and ferries shuttle between the

mainland, Hong Kong Island, and all other major outlying islands.

Government

Hong Kong and Kowloon The city of Hong Kong, left,

faces Victoria Harbor on the northern part of Hong Kong Island. Kowloon, right,

is situated across the harbor on the mainland. Both are part of the Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China. Yang Liu/Corbis |

|

|

|

Kowloon, administrative area of Hong Kong,

forming a peninsula of the mainland China coast, across Victoria Harbor from

Hong Kong Island. Kowloon is an important transportation, manufacturing, and

tourist area, as well as a densely populated residential and commercial zone.

It has a total area of 11.9 sq km (4.6 sq mi). Kowloon

is the site of Hong Kong Baptist University, founded in 1965, and two

polytechnic institutions. There is a large mosque on the main commercial

artery, Nathan Road, and several small parks, including Kowloon Park, where

the Hong Kong Museum of History is located. The Hong Kong Cultural Center,

the Space Museum, and the Hong Kong Museum of Art are located on the

waterfront at the southern tip of the peninsula. Regular

and frequent ferry service connects Kowloon to Hong Kong Island. A motor

vehicle and mass transit tunnel runs under Victoria Harbor. Kowloon was part

of China until 1860, when it was ceded to Britain following China’s defeat in

the Second Opium War (see Opium Wars). The British initially used the

area to protect Victoria Harbor and stationed colonial troops there, but

Kowloon also quickly developed important port facilities. More significant

development of Kowloon occurred after 1898, when China leased the adjacent

New Territories to Britain. This added a substantial population and land area

to support commercial and industrial development in Kowloon. It also

permitted urban expansion northward, beyond the original Kowloon region, to

include the area called New Kowloon. By 1910 a railway had been completed

between Kowloon and the Chinese city of Guangzhou, and Kowloon became an

important transit point for trade and traffic with China. Port and storage

facilities expanded, industrial growth soon followed, and Kowloon developed

as one of several important manufacturing sites in Hong Kong. Since the

1950s, Kowloon has continued to grow and prosper as Hong Kong has developed

into an important Asian market. Kowloon, like the rest of Hong Kong, returned

to Chinese control on July 1, 1997. Population, including New Kowloon (1991)

2,030,683. |

|

|

Prior to July 1, 1997,

Hong Kong was a British dependent territory. A British-appointed governor,

representing the British crown, headed the Hong Kong government and exercised

authority over civil and military matters. An Executive Council advised the

governor on important matters, and a 60-member Legislative Council (known as

Legco) enacted laws and oversaw the budget. With the territory’s transfer to

China in 1997, leadership passed from the last British governor, Chris Patten,

to a Chinese chief executive, Tung Chee-hwa.

The terms of the transfer

to China were based on a “one country, two systems” concept, under which Hong

Kong is allowed a high degree of autonomy, charting its own course with the

exception of foreign affairs and defense. The Hong Kong SAR is governed under a

“mini-constitution” called the Basic Law, which guarantees that the capitalist

system and way of life in Hong Kong will remain unchanged for 50 years after

the transfer to China. Under the Basic Law, a chief executive, appointed to a

maximum of two five-year terms, heads the government of the Hong Kong SAR. An

election committee, whose members are appointed by China, selects the chief

executive. The chief executive presides over the Executive Council, whose

members assist the chief executive in policy-making decisions.

The lawmaking body of

the Hong Kong SAR is the Legislative Council, which is comprised of 60 members

who serve four-year terms. In the 2004 legislative elections 30 seats went to

candidates who were directly elected by a system of proportional representation

(in which seats are awarded to a political party in proportion to the number of

popular votes it receives), and 30 seats were determined by elections within

“functional constituencies” comprising professional and special interest

groups. The judiciary of the Hong Kong SAR is independent, and laws are based

on English common law and the rules of equity. Judges are appointed by the

chief executive.

New Territories, area of Hong Kong that lies mostly on

the mainland China coast north of Kowloon and south of Guangdong Province. The

New Territories also includes Lantau Island (also called Tai Yue Island) and

other surrounding smaller islands. The total land area of the New Territories

is about 950 sq km (about 365 sq mi), and the surrounding territorial waters

cover approximately 1,500 sq km (approximately 580 sq mi). The New Territories

was leased by China to the United Kingdom in 1898; it was returned to China on

July 1, 1997, along with the rest of Hong Kong.

In

1991, the New Territories had a population of 2,374,818accounting for nearly 42

percent of Hong Kong’s population. The overall population density is about

2,500 persons per sq km (about 6,500 per sq mi), although the people are

unevenly distributed, with most living in a number of new towns on the

mainland. These towns and industrial estates have been created to support

industrial development in the New Territories and to decentralize the

population from the more crowded areas of Kowloon and Hong Kong Island. Tsuen

Wan was the first and largest of these new towns. Other rapidly growing ones

include Tuen Mun, Sha Tin, Yuen Long, Tai Po, and Fanling.

The

Chinese University of Hong Kong, founded in 1963, is located in Sha Tin. Lantau

Island has several Buddhist monasteries, with Po Lin Monastery being the

largest. Recreational facilities include the Sha Tin Racecourse, the Hong Kong

Golf Club in Fanling, and an amusement park.

The

British acquisition of the New Territories in 1898 set the stage for Hong

Kong’s rapid growth during the 20th century. Since the 1950s, Hong Kong has

established industrial zones, planned communities, and new port facilities in

the New Territories. It has also expanded existing port facilities. Although

farming has declined, there are still nearly 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) of

active farmland, which are used for poultry and egg production, and for growing

vegetables and flowers.

There

is a large container port at Kwai Chung and a new container terminal is planned

for Lantau Island; it will connect to a river port terminal for the

transshipment of containers to Guangzhou, a mainland city in Guangdong

Province. A substantial road and highway network connects the major new towns

of the New Territories, and the main rail line to Guangzhou links Lo Wu,

Fanling, Tai Po, and Sha Tin to Kowloon. A light rail line connects Tuen Mun

and Yuen Long in the western part of the New Territories. An international

airport opened on Chek Lap Kok, an islet near Lantau, in July 1998. An express

highway and railway link the new airport with the New Territories and Kowloon.

Farmers

lived in the area that is now the New Territories before Britain leased the

region from China in 1898 to create a buffer zone between Victoria Harbor and

China proper. Britain sought the land less out of fear of China, than from

concern over the rapid expansion of other colonial powers—Germany, France,

Japan, and Russia—in China.

In

addition to providing more space for an adequate military defense, the New

Territories added a substantial rural population. The region also provided land

for food and timber production, and a much-needed catchments area for fresh

water supplies. In the 1980s the impending expiration of Britain’s lease on the

New Territories necessitated negotiations between Britain and China, and the

Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed in 1984. In it, Britain agreed to

return Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty on July 1, 1997.

Boat People

In

September, British, Vietnamese, and UN officials reached agreement for the

repatriation of Vietnamese asylum-seekers in Hong Kong. The agreement called

for return of those who while 'not volunteering' were nevertheless 'not opposed

to repatriation.' An estimated 54,000 Vietnamese currently lived in camps in

the British colony and were ineligible for resettlement in the West. A previous

voluntary return program, beginning in March 1989, had been moving slowly. In

December 1989, 51 boat people were involuntarily repatriated from Hong Kong to

Vietnam, in a move that drew international criticism. An accord between China

and Britain to build a new airport in Hong Kong actually lessened the

territory's autonomy by providing Beijing with a direct say in Hong Kong's

domestic affairs. The first forced repatriation of Vietnamese boat people since

1989 began in the fall.

Fears of the Future

There were

also calls for the more rapid introduction of democracy in the colony. British

Foreign Secretary John Major announced in September that his government would

give Hong Kong a bill of rights intended to preserve the freedoms China had

agreed to retain for the territory and that it would work for direct election

of half of the legislature by 1995. Political leaders have also called on China

to delay the promulgation of the final Basic Law for post-1997 Hong Kong and to

reconsider some of its provisions. Of particular concern was the plan to

station Chinese troops from the People's Liberation Army in the territory after

1997, as provided both the draft Basic Law and in the Sino-British Joint

Declaration on the Future of Hong Kong. Talks between Chinese and British

officials on the future of the territory were to take place late in the year.

Hong Kong’s Future

After 143

years of colonial rule, Great Britain on September 26 initialed an agreement

with China providing for China's resumption of sovereignty over Hong Kong on

July 1, 1997, when Britain's lease over 92 percent of the territory's land area

expires. Two years of negotiations were concluded with a 'joint declaration,'

which stipulated that Hong Kong would enjoy a 'high degree of autonomy' in all

areas except foreign affairs and defense, as a 'special administrative region'

of China after 1997. Under the accord, to which China committed itself for a

period of 50 years, the government of Hong Kong would be composed of local

inhabitants, with an elected legislature, an independent judiciary, and a chief

executive appointed by Peking. The current social and economic system in Hong

Kong, as well as the territory's 'lifestyle,' would remain unchanged for the

50-year period. China hoped that this 'one country, two systems' formula could

also be applied to Portuguese-administered Macao and to Taiwan.

Hong Kong Under Chinese Sovereignty

|

|

|

|

The Return of Hong Kong to China

NBC News Archives

Chris Patten

Chris Patten was the last British

governor of Hong Kong, serving from 1992 until the territory reverted to

Chinese rule in 1997.

Dennis Brack/Black Star

At the

stroke of midnight, local time, on June 30, 1997, Hong Kong became a special

administrative region of the People’s Republic of China, after more than 150

years as a British colony. Hong Kong was ceded to Great Britain when Great

Britain defeated China in the First Opium War (1839-1842). Under the

Sino-British Joint Declaration (1984), Great Britain agreed to return all of

Hong Kong to China in 1997. Presented here are excerpts from a translation of

the speech made by Chinese President Jiang Zemin at the flag-changing ceremony.

The national

flag of the People's Republic of China and the regional flag of the Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China have now

solemnly risen over this land.… This is both a festival for the Chinese nation

and a victory for the universal cause of peace and justice.

Thus, July

1, 1997, will go down in the annals of history as a day that merits eternal

memory. The return of Hong Kong to the motherland after going through a century

of vicissitudes indicates that from now on, the Hong Kong compatriots have

become true masters of this Chinese land and that Hong Kong has now entered a

new era of development.

History will

remember, former Chinese paramount leader, Mr. Deng Xiaoping for his creative

concept of 'one country, two systems.' It is precisely along the course

envisaged by this great concept that we have successfully resolved the Hong

Kong question through diplomatic negotiations and finally achieved Hong Kong's

return to the motherland….

On this

solemn occasion, I wish to extend my cordial greetings and best wishes to the 6

million or more Hong Kong compatriots who have now returned to the embrace of

the motherland.

After the

return of Hong Kong, the Chinese government will unswervingly implement the

basic policies of 'one country, two systems,' 'Hong Kong people administering

Hong Kong,' and 'a high degree of autonomy' and keep the previous socioeconomic

system and way of life of Hong Kong unchanged and its laws basically unchanged.

After the

return of Hong Kong, the central … government shall be responsible for the

foreign affairs relating to Hong Kong and the defense of Hong Kong. The Hong

Kong Special Administrative Region shall be vested, in accordance with the

Basic Law, with executive power, legislative power, and independent judicial

power, including that of final adjudication. The Hong Kong residents shall

enjoy various rights and freedoms according to law. The Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region shall gradually develop a democratic system that suits

Hong Kong's reality.

After the

return, Hong Kong will retain its status of a free port, continue to function

as an international financial, trade, and shipping center, and maintain its

economic and cultural ties with other countries, regions, and relevant

international organizations. The legitimate economic interests of all countries

and regions in Hong Kong will be protected by law.

I hope that

all the countries and regions that have investment and trade interests here will

continue to work for the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong

compatriots have a glorious patriotic tradition. Hong Kong's prosperity today,

in the final analysis, has been built by Hong Kong compatriots. It is also

inseparable from the development and support of the mainland. I am confident

that with the strong backing of the entire Chinese people, the government of

the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and Hong Kong compatriots will be

able to manage Hong Kong well, build it up, and maintain its long-term

prosperity and stability, thereby ensuring Hong Kong a splendid future.

Summary

The first

permanent settlement in what is today Hong Kong probably occurred about 2,000

years ago during the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220). The British, became

interested in Hong Kong in the early 19th century. The trade of opium, a highly

profitable product for British merchants and eventually an illegal import into

China, led to the Opium Wars and Britain’s acquisition of Hong Kong. One year

later, China and Britain signed the Treaty of Nanjing (Nanking) which ceded

Hong Kong Island and adjacent small islands in perpetuity to Britain. Treaty

disputes and other incidents led to the Second Opium War in 1856, also won by

Britain. The conflict ended with the ratification of the Treaty of Tianjin in

1860. In 1898 China leased the New Territories to Britain for 99 years, adding

more than 900 sq km (350 sq mi) of land and considerable territorial waters to

Hong Kong.

The New

Territories was leased by China to the United Kingdom in 1898; it was returned

to China on July 1, 1997, along with the rest of Hong Kong. The British

acquisition of the New Territories in 1898 set the stage for Hong Kong’s rapid

growth during the 20th century. Farmers lived in the area that is now the New

Territories before Britain leased the region from China in 1898 to create a

buffer zone between Victoria Harbor and China proper. Britain sought the land

less out of fear of China, than from concern over the rapid expansion of other

colonial powers—Germany, France, Japan, and Russia—in China.

Hong Kong

grew slowly during the 19th century, although gaining the New Territories added

a substantial rural population. By 1900 there were perhaps as many as 100,000

people. This wave of population growth

was halted during World War II (1939-1945) when Japanese forces invaded and

occupied Hong Kong for almost four years. Hong Kong’s greatest growth and

development occurred after the Communist takeover of China in 1949, when the

commercial and shipping functions of Guangzhou and Shanghai shifted to Hong

Kong.

Hong Kong

served as China’s window to the world during the Chinese administration of Mao

Zedong. After Mao’s death in 1976, Hong Kong’s role as a banker to China, and

as its supplier of information, technology, and capital, intensified. The

British territory was to become, in other words, Chinese. The bastion of

capitalism was to fall, under the authority of Communists. Six million people,

whether they liked it or not, were to watch their nationalities and their

citizenships and their futures change in the blink of an eye.

In 1990, the

literacy rate in Hong Kong was virtually 100 percent; in China, some 182

million people out of an estimated population of about 1.2 billion could not

read or write.

The British

colonial period was partly responsible for the many freedoms that existed in

Hong Kong—freedom of the press, of religion, of association, of speech—its

coming end was a cause for grave concern.

A challenge

for Hong Kong and China—two societies that have evolved over the last 150 years

into entities that are dramatically different from each other—to unite and

create a blend of the two ways of life.

The first

tea imported into Britain came from China via the Portuguese, who had a trading

post in their colony of Macao on the southeastern coast of China. Before the

demand was so huge, it was decided that Britain should import the tea itself,

rather than let the Portuguese act as the middlemen.

Under the

circumstances it was inevitable that the British should intensify the

fortification of Hong Kong, which became legitimate on the expiration of the

Washington Naval Treaty at the end of 1936.

Hong Kong is

no longer considered an important strategic outpost of the Empire. In case of a

world war in which Britain and Japan were involved, it was agreed that the