June 12, 2006

The Tornado’s Potential

Destruction

By Dr. Frank J. Collazo

Introduction:

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air extending

from within a thundercloud down to ground level. The strongest tornadoes may sweep houses from their foundations,

destroy brick buildings, toss cars and school buses through the air, and even

lift railroad cars from their tracks.

Tornadoes vary in diameter from tens of meters to nearly 2 km (1 mi),

with an average diameter of about 50 m (160 ft). Most tornadoes in the northern hemisphere create winds that blow

counterclockwise around a center of extremely low atmospheric pressure. In the southern hemisphere the winds

generally blow clockwise. Peak wind

speeds can range from near 120 km/h (75 mph) to almost 500 km/h (300 mph). The forward motion of a tornado can range

from a near standstill to almost 110 km/h (70 mph).

What is a

tornado? According to the Glossary of

Meteorology (AMS 2000) a tornado is "a violently rotating column of air,

pendant from a cumuliform cloud or underneath a cumuliform cloud, and often

(but not always) visible as a funnel cloud." Literally, in order for a vortex to be classified as a tornado,

it must be in contact with the ground and the cloud base. Weather scientists haven't found it so

simple in practice, however, to classify and define tornadoes. For example, the difference is unclear

between a strong mesocyclone (parent thunderstorm circulation) on the ground,

and a large, weak tornado. There is also disagreement as to whether separate

touchdowns of the same funnel constitute separate tornadoes.

It is well known that a tornado may not have a visible

funnel. Also, at what wind speed of the

cloud-to-ground vortex does a tornado begin?

How close must two or more different tornadic circulations become to

qualify as a one multiple-vortex tornado instead of separate tornadoes? There are no firm answers.

Figure 2 - Formation of a

Tornado

Many tornadoes, including the strongest ones, develop from a special type of thunderstorm known as a super-cell. A super-cell is a long-lived, rotating thunderstorm 10 to 16 km (6 to 10 mi) in diameter that may last several hours, travel hundreds of miles, and produce several tornadoes. Super-cell tornadoes are often produced in sequence, so that what appears to be a very long damage path from one tornado may actually be the result of a new tornado that forms in the area where the previous tornado died. Sometimes, tornado outbreaks occur, and swarms of super-cell storms may occur. Each super-cell may spawn a tornado or a sequence of tornadoes.

The complete process of tornado formation in super-cells

is still debated among meteorologists.

Scientists generally agree that the first stage in tornado formation is

an interaction between the storm updraft and the winds. An updraft is a current of warm, moist air

that rises upward through the thunderstorm.

The updraft interacts with the winds, which must change with height in

favorable ways for the interaction to occur.

This interaction causes the updraft to rotate at the middle levels of

the atmosphere. The rotating updraft,

known as a meso-cyclone, stabilizes the thunderstorm and gives it its

long-lived super- cell characteristics.

cell characteristics.

The next stage is the development of a strong downdraft (a current of cooler air that moves in a downward direction) on the backside of the storm, known as a rear-flank downdraft. It is not clear whether the rear-flank downdraft is induced by rainfall or by pressure forces set up in the storm, although it becomes progressively colder as the rain evaporates into it. This cold air moves downward because it is denser than warm air. The speed of the downdraft increases and the air plunges to the ground, where it fans out at speeds that can exceed 160 km/h (100 mph). The favored location for the development of a tornado is at the area between this rear-flank downdraft and the main storm updraft. However, the details of why a tornado should form there are still not clear.

The same condensation process that creates tornadoes makes visible the generally weaker sea-going tornadoes, called waterspouts. Waterspouts occur most frequently in tropical waters.

Types of Tornadoes

Tornado Twister: A tornado that's 500 meters in diameter

looks a lot more ominous than the average twister, which is "only"

150 meters across. But tornado size is

not related to wind speed, or to damage intensity. Instead, wind speed increases along with the difference between

atmospheric pressure inside the funnel and the pressure outside it (the core

pressure difference). The larger the

difference in atmospheric pressure between the core and the surrounding air,

the faster the winds. But at a given wind speed, a larger

tornado will do more total damage.

Gustnado: A gustnado is a small and

usually weak whirlwind, which forms as an eddy in thunderstorm outflows. They do not connect with any cloud-base

rotation and are not tornadoes. But

because gustnadoes often have a spinning dust cloud at ground level, they are

sometimes wrongly reported as tornadoes.

Gustnadoes can do minor damage such as: break windows and tree limbs,

overturn trashcans and toss lawn furniture, and should be avoided.

Wedge" Tornado and a "Rope" Tornado: These are slang terms

often used by storm observers to describe tornado shape and appearance. Remember, the size or shape of a tornado

does not say anything certain about its strength!

Wedge tornadoes simply appear to be at least as wide as they are

tall (from ground to ambient cloud base).

Rope tornadoes are

very narrow, often sinuous or snake-like in form. Tornadoes often (but not always!) assume the "rope"

shape in their last stage of life, and the cloud rope may even break up into

segments. Again, tornado shape and size

does not signal strength! Some rope tornadoes

can still do violent damage of F4 or F5.

A "Satellite" Tornado: Is it a kind of multi-vortex tornado? No.

There are important distinctions between satellite and multiple-vortex

tornadoes. A satellite tornado develops

independently from the primary tornado -- not inside it, as does a suction

vortex. The tornadoes remain separate

and distinct as the satellite tornado orbits its much larger companion within

the same mesocyclone. Their cause is

unknown; but they seem to form most often in the vicinity of exceptionally

large and intense tornadoes.

Land Spout: This is storm-chaser slang for a non-super cell

tornado. So-called "land

spouts" resemble waterspouts in that way, and also in their typically

small size and weakness compared to the most intense tornadoes. But "land spouts" are tornadoes by

definition, and they are capable of doing significant damage and killing

people.

Spinning Like Dynamo Energy (Energy Generation Basics): Scientifically speaking,

it's the ability to do work (that's one of the plainest definitions in

science). Energy takes many forms,

including chemical, kinetic, potential and thermal. Energy can change forms.

You know the drill: Solar energy creates chemical energy in plants,

which eventually become petroleum. When

your Nash Metropolitan burns gasoline, it becomes heat energy, which then

becomes kinetic energy. And when

(should we say "if") your brakes stop that Nash, the kinetic energy

is transformed again into heat energy.

A different set of energy transformations power the furious winds

of a twister. Like your car, tornadoes

also get their energy from the sun.

When the sun warms the ocean, water evaporates and carries potential

energy, called the latent heat of vaporization, into the atmosphere. When the water vapor rises, cools and

condenses inside a thunderstorm, the latent heat of condensation is

released. According to Robert

Davies-Jones of the National Severe Storms Laboratory, this latent heat is the

biggest single source of energy in a thunderstorm. When the latent heat is released, it warms the rising air,

causing a difference in density that pushes the air up at the extreme speeds

needed to create a tornado.

Tornadoes release a boatload of energy, says Davies-Jones. A tornado with wind speeds of 200 mph

releases kinetic energy at the rate of 1 billion watts -- equal to the electric

output of a pair of large nuclear reactors.

But that's just processed cheese compared to the large thunderstorms

that can spawn tornadoes. These

monsters release latent heat at the rate of 40 trillion watts -- 40,000 times

as powerful as the puny twister, Davies-Jones says.

Virtuous Vortex: A tornado is a type of vortex -- a

spinning column of air with some water vapor.

You can make a tornado quite easily.

Take

two 2-liter soda bottles, fill one with water and some food coloring, and

connect the bottles with a "tornado tube" (available from Edmund Scientific and many toy

stores). If you're feeling cheap,

Dorothy suggests old-fashioned duct tape.

One tube will be upside down, the other right side up.

Move

the water-filled bottle to the top, give the bottles a twist, and a vortex will

flow into the lower bottle.

How do you forecast tornadoes? This is a very simple question with no

simple answer! Here is a very generalized view from the perspective of a severe

weather forecaster: When predicting severe weather (including tornadoes) a day

or two in advance, we look for the development of temperature and wind flow

patterns in the atmosphere which can cause enough moisture, instability, lift,

and wind shear for tornadic thunderstorms.

Those are the four needed ingredients. But it is not as easy as it sounds. "How much is enough" of those is not a hard fast

number, but varies a lot from situation to situation -- and sometimes is unknown!

A large variety of weather patterns can lead to tornadoes; and

often, similar patterns may produce no severe weather at all. To further complicate it, the various

computer models we use days in advance can have major biases and flaws when the

forecaster tries to interpret them on the scale of thunderstorms. As the event gets closer, the forecast

usually (but not always) loses some uncertainty and narrows down to a more

precise threat area. Real-time weather

observations -- from satellites, weather stations, balloon packages, airplanes,

wind profilers and radar-derived winds -- become more and more critical the

sooner the thunderstorms are expected; and the models become less important.

To figure out

where the thunderstorms will form, we must do some hard, short-fuse detective

work: Find out the location, strength and movement of the fronts, dry lines,

outflows, and other boundaries between air masses which tend to provide

lift. Figure out the moisture and

temperatures -- both near ground and aloft -- which will help storms form and

stay alive in this situation. Find the

wind structures in the atmosphere, which can make a thunderstorm, rotate as a

super cell, and then produce tornadoes.

Make an educated guess where the most favorable combination of

ingredients will be and when; then draw the areas and type the forecast.

What direction do tornadoes come from? Does the region of the US

play a role in path direction?

Tornadoes can appear from any direction. Most move from southwest to northeast, or west to east. Some tornadoes have changed direction amid

path, or even backtracked. [A tornado can double back suddenly, for example,

when its bottom is hit by outflow winds from a thunderstorm's core.] Some areas of the US tend to have more paths

from a specific direction, such as northwest in Minnesota or southeast in

coastal south Texas. This is because of

an increased frequency of certain tornado-producing weather patterns (say,

hurricanes in south Texas, or northwest-flow weather systems in the upper

Midwest).

Hail leading tornado rain?

Lightning? Utter silence? Not

necessarily, for any of those. Rain,

wind, lightning, and hail characteristics vary from storm to storm, from one

hour to the next, and even with the direction the storm is moving with respect

to the observer. While large hail can

indicate the presence of an unusually dangerous thunderstorm, and can happen

before a tornado, don't depend on it.

Hail, or any particular pattern of rain, lightning or calmness, is not a

reliable predictor of tornado threat.

How do tornadoes dissipate? The details are still debated by tornado

scientists. We do know tornadoes need a

source of instability (heat, moisture, etc.) and a larger-scale property of

rotation of vortices to keep going.

There are a lot of processes around a thunderstorm, which can possibly

rob the area around a tornado of either instability or vorticity. One is relatively cold outflow -- the flow

of wind out of the precipitation area of a shower or thunderstorm. Many tornadoes have been observed to go away

soon after being hit by outflow. For

decades, storm observers have documented the death of numerous tornadoes when

their parent circulations (meso-cyclones) weaken after they become wrapped in

outflow air -- either from the same thunderstorm or a different one. The irony

is that some kinds of thunderstorm outflow may help to cause tornadoes, while

other forms of outflow may kill tornadoes.

How long does a tornado last? Tornadoes can last from several seconds to

more than an hour. The longest-lived

tornado in history is really unknown, because so many of the long-lived

tornadoes reported from the early 1900s and before are believed to be tornado

series instead. Most tornadoes last

less than 10 minutes.

How close to a tornado does the barometer drop? And how far does it drop? It varies. A barometer

can start dropping many hours or even days in advance of a tornado if there is

low pressure on a broad scale moving into the area. Strong pressure falls will often happen as the mesocyclone

(parent circulation in the thunderstorm) moves overhead or nearby. The biggest drop will be in the tornado

itself, of course. It is very hard to

measure pressure in tornadoes since most weather instruments can't

survive.

A few low-lying, armored

probes called "turtles" have been placed successfully in

tornadoes. This includes one deployment

on 15 May 2003 by engineer/storm chaser Tim Samaras, who recorded pressure fall

of over 40 millibars through an unusually large tornado. On 24 June 2003, another of Tim's probes

recorded a 100 millibars pressure plunge in a violent tornado near Manchester,

SD. Despite those spectacular results,

and a few fortuitous passes over barometers through history, we still do not

have a database of tornado pressures big enough to say much about average tornado

pressures or other barometric characteristics.

What is a waterspout? A waterspout is a tornado over water --

usually meaning non-super cell tornadoes over water. Waterspouts are common along the southeast U.S. coast --

especially off southern Florida and the Keys -- and can happen over seas, bays

and lakes worldwide. Although

waterspouts are always tornadoes by definition; they don't officially count in

tornado records unless they hit land.

They are smaller and weaker than the most intense Great Plains

tornadoes, but still can be quite dangerous.

Waterspouts can overturn small boats, damage ships, do significant

damage when hitting land, and kill people.

The National Weather Service will often issue special marine warnings

when waterspouts are likely or have been sighted over coastal waters, or

tornado warnings when waterspouts can move onshore.

How are tornadoes in the northern hemisphere different from

tornadoes in the southern hemisphere? The sense of rotation is usually the

opposite. Most tornadoes, but not all,

rotate cyclonically, which is counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere and

clockwise south of the equator.

Anti-cyclonic tornadoes (clockwise-spinning in the northern hemisphere)

have been observed, however -- usually in the form of waterspouts, non-super

cell land tornadoes, or anticyclone whirls around the rim of a super cell’s

mesocyclone. There have been several

documented cases of cyclonic and anticyclone tornadoes under the same

thunderstorm at the same time.

Anti-cyclonically, rotating super cells with tornadoes are extremely

rare; but one struck near Sunnyvale, CA, in 1998. Remember, "cyclonic" tornadoes spin counter-clockwise

in the northern hemisphere.

What is a multi-vortex tornado?

Multi-vortex (a.k.a. multiple-vortex) tornadoes contain two or more small,

intense sub-vortices orbiting the center of the larger tornado

circulation. When a tornado does not

contain too much dust and debris, they can sometimes be spectacularly visible. These vortices may form and die within a few

seconds, sometimes appearing to train through the same part of the tornado one

after another. They can happen in all

sorts of tornado sizes, from huge "wedge" tornadoes to narrow

"rope" tornadoes.

Sub-vortices are the cause of most of the narrow, short, extreme swaths

of damage that sometimes arc through tornado tracks. From the air, they can preferentially mow down crops and stack

the stubble, leaving cycloid marks in fields. Multi-vortex tornadoes are the

source of most of the old stories from newspapers and other media before the

late 20th century, which told of several tornadoes seen together at once.

Tornado

Watching: The picture depicted below of a

meteorologist tracking a tornado as part of ongoing weather observations to

better understand the earth’s atmosphere.

Since the 19th century, scientific forecasting has greatly

improved. Weather radar can detect and

track tornados, hurricanes, and other severe storms.

Figure 1 - Photo Researchers, Inc./Howard Bluestein/Science

Source-Tornado Tracking

Visibility of a Tornado: A tornado becomes visible when a

condensation funnel made of water vapor (a funnel cloud) forms in extreme low

pressures, or when the tornado lofts dust, dirt, and debris upward from the

ground. A mature tornado may be

columnar or tilted, narrow or broad—sometimes so broad that it appears as if

the parent thundercloud itself had descended to ground level. Some tornadoes resemble a swaying elephant's

trunk. Others, especially very violent

ones, may break into several intense suction vortices—intense swirling masses

of air—each of which rotates near the parent tornado. A suction vortex may be only a few meters in diameter, and thus

can destroy one house while leaving a neighboring house relatively unscathed.

Tornadoes Studied by Scientists: Scientists study tornadoes to gain a better

understanding of their formation, behavior, and structure. Scientists who study tornadoes have a

variety of powerful research tools at their disposal. Advances in computer technology make it possible to simulate the

thunderstorms that spawn tornadoes using computer models running on desktop

computers. Doppler radars, which detect

the rain in clouds, allow meteorologists, scientists who study weather, to

"see" the winds inside the storms that spawn tornadoes. Modern video camera footage and reports from

trained storm-spotters provide an unprecedented amount of high-quality tornado

documentation. These tools all

contribute greatly to the scientific understanding of tornadoes. This information may eventually lead to

increased tornado warning times, better guidelines for building construction

(especially schools) and improved safety tips.

How is tornado damage rated? The most widely used method worldwide for

over three decades was the F-scale developed by Dr. T. Theodore Fujita. In the U.S., and probably elsewhere within a

few years, the new Enhanced F-scale is becoming the standard for assessing

tornado damage. In Britain, there is a

scale similar to the original F-scale but with more divisions; for more info,

go to the TORRO scale website. In both

original F- and TORRO-scales, the wind speeds are based on calculations of the

Beaufort wind scale and have never been scientifically verified in real

tornadoes. Enhanced F-scale winds are

derived from engineering guidelines but still are only judgmental

estimates. Because:

- Nobody

knows the "true" wind speeds at ground level in most tornadoes,

and

- The amount

of wind needed to do similar-looking damage can vary greatly, even from

block to block or building to building,

Damage rating is (at best) is an exercise in educated

guessing. Even experienced

damage-survey meteorologists and wind engineers can and often do disagree among

themselves on a tornado's strength.

Damage Assessment Protection by a Tornado: Many houses close to a twister are damaged or destroyed by wind, rain and flying debris. These homes and their occupants can benefit from simple, relatively cheap measures to drastically reduce damage, Wolfe adds. Many of these improvements concern the roof, which often fails first in windstorms. Once that happens, Wolfe says, torrential rain can soak the insulation and drywall and the walls, no longer braced from above, can collapse.

![]() Roof shingles

are usually the first to go, Wolfe says.

Shingles near roof edges, which face the worst winds, should be set in

special mastic during re-shingling.

Roof shingles

are usually the first to go, Wolfe says.

Shingles near roof edges, which face the worst winds, should be set in

special mastic during re-shingling.

![]() Roof sheathing, usually a material like plywood, should be

nailed securely to the rafters. Nails

should be 6 inches apart at the edges and 12 inches apart elsewhere.

Roof sheathing, usually a material like plywood, should be

nailed securely to the rafters. Nails

should be 6 inches apart at the edges and 12 inches apart elsewhere.

![]() Rafter fastening is critical.

These angled beams, which support the roof sheathing, were traditionally

nailed to the walls. This is extremely

weak, Wolfe says, partly because the nails tend to split the rafters. Simple, cheap "hurricane clips"

make a connection that is 5 to 15 times stronger.

Rafter fastening is critical.

These angled beams, which support the roof sheathing, were traditionally

nailed to the walls. This is extremely

weak, Wolfe says, partly because the nails tend to split the rafters. Simple, cheap "hurricane clips"

make a connection that is 5 to 15 times stronger.

![]() Foundation anchors keep a house from blowing away in one piece. Even though Wisconsin’s building code

required that houses be bolted to foundations, Wolfe says the attachments were

missing from many wrecked homes in Barneveld.

Although builders thought the attachments were unnecessary, he says, the

tornado proved them wrong.

Foundation anchors keep a house from blowing away in one piece. Even though Wisconsin’s building code

required that houses be bolted to foundations, Wolfe says the attachments were

missing from many wrecked homes in Barneveld.

Although builders thought the attachments were unnecessary, he says, the

tornado proved them wrong.

Mobile Homes: Mobile homes present special problems in tornadoes. The best advice is to leave them for

underground shelter, says James McDonald, professor of civil engineering at

Texas Tech University in Lubbock, who also directs the Institute for Disaster

Research. "There's not a whole lot

you can do because of the way they are constructed. It's a very lightweight structure with a large, exposed surface

area ... that's built with very little margin for error." A 1993 federal regulation, passed in

response to Hurricane Andrew, raised building standards. New mobile homes must withstand 30 to 40

percent faster winds, McDonald says (previously, homes were supposed to survive

winds of only 60 mph). Stronger

fastenings must be used inside the home, especially at exterior corners. But a mobile home that remains intact must

also remain in place.

The standard anchoring technique, McDonald says, is to drive big

steel screws into the ground. "But

there's a catch-22. If the ground is

soft enough for the anchor to penetrate, the soil is too soft to prevent it

from pulling out. If the ground is

stronger, the stake won't go in deeply enough." McDonald (see "Review of Standard Practice. ..." In the bibliography) notes that "95

percent of mobile homes are never moved after they are placed." Thus he advocates anchoring mobile homes to

concrete foundations, an expensive measure but one that can be done to existing

homes. Still, given the drawbacks of

lightweight construction and lack of a basement, McDonald says he would not

feel comfortable riding out a tornado warning in a new-standard mobile home,

even if it was bolted to a concrete foundation.

Classification of Tornadoes

What is the original F-scale? Dr. T. Theodore Fujita developed a damage

scale (Fujita 1971, Fujita and Pearson 1973) for winds, including tornadoes,

which was supposed to relate the degree of damage to the intensity of the wind. This scale was the result. The original F-scale should not be used

anymore, because it has been replaced by an enhanced version. Tornado wind speeds are still largely

unknown; and the wind speeds on the original F-scale have never been

scientifically tested and proven. Different

winds may be needed to cause the same damage depending on how well built a

structure is, wind direction, wind duration, battering by flying debris, and a

bunch of other factors.

Also, the process of rating the damage itself is largely a

judgment call -- quite inconsistent and arbitrary (Doswell and Burgess,

1988). Even meteorologists and

engineers highly experienced in damage survey techniques often came up with

different F-scale ratings for the same damage.

Even with all its flaws, the original F-scale was the only widely used

tornado rating method for over three decades.

The enhanced F-scale takes effect 1 February 2007.

What is the Enhanced F-scale? The Enhanced F-scale is a much more precise

and robust way to assess tornado damage than the original. It classifies F0-F5 damage as calibrated by

engineers and meteorologists across 28 different types of damage indicators

(mainly various kinds of buildings, but also a few other structures as well as

trees). The idea is that a "one

size fits all" approach just doesn't work in rating tornado damage, and

that a tornado scale needs to take into account the typical strengths and

weaknesses of different types of construction.

This is because the same wind does different things to different kinds

of structures. In the Enhanced F-scale,

there will be different, customized standards for assigning any given F rating

to a well built, well anchored wood-frame house compared to a garage, school,

skyscraper, unanchored house, barn, factory, utility pole or other type of

structure.

In a real-life tornado track, these ratings can be mapped together

more smoothly to make a damage analysis.

Of course, there still will be gaps and weaknesses on a track where

there was little or nothing to damage, but such problems will be less common

than under the original F-scale. As

with the original F-scale, the enhanced version will rate the tornado as a

whole based on most intense damage within the path. The enhanced F-scale takes effect 1 February 2007.

The

following table is an update to the original F-scale by

a team of meteorologists and wind engineers, to be implemented in the U.S. on 1

February 2007.

Table I - Enhanced F

Scale for Tornado Damage

|

Fujita Scale |

Derived EF Scale |

Operational

EF Scale |

||||

|

F Number |

Fastest 1/4-mile (mph) |

3 Second Gust (mph) |

EF Number |

3 Second Gust (mph) |

EF Number |

3 Second Gust (mph) |

|

0 |

40-72 |

45-78 |

0 |

65-85 |

0 |

65-85 |

|

1 |

73-112 |

79-117 |

1 |

86-109 |

1 |

86-110 |

|

2 |

113-157 |

118-161 |

2 |

110-137 |

2 |

111-135 |

|

3 |

158-207 |

162-209 |

3 |

138-167 |

3 |

136-165 |

|

4 |

208-260 |

210-261 |

4 |

168-199 |

4 |

166-200 |

|

5 |

261-318 |

262-317 |

5 |

200-234 |

5 |

Over 200 |

Table

II - Enhanced F Scale Damage Indicators

Number (Details Linked)

Damage Indicator Abbreviation

|

Number (Details Linked) |

Damage Indicator |

Abbreviation |

|

Small barns, farm

outbuildings |

SBO |

|

|

One- or two-family

residences |

FR12 |

|

|

Single-wide mobile

home (MHSW) |

MHSW |

|

|

Double-wide mobile

home |

MHDW |

|

|

Apt, condo, townhouse

(3 stories or less) |

ACT |

|

|

Motel |

M |

|

|

Masonry apt. or motel |

MAM |

|

|

Small retail bldg.

(fast food) |

SRB |

|

|

Small professional

(doctor office, branch bank) |

SPB |

|

|

Strip mall |

SM |

|

|

Large shopping mall |

LSM |

|

|

Large, isolated

("big box") retail bldg. |

LIRB |

|

|

Automobile showroom |

ASR |

|

|

Automotive service

building |

ASB |

|

|

School - 1-story

elementary (interior or exterior halls) |

ES |

|

|

School - jr. or sr.

high school |

JHSH |

|

|

Low-rise (1-4 story)

bldg. |

LRB |

|

|

Mid-rise (5-20 story)

bldg. |

MRB |

|

|

High-rise (over 20

stories) |

HRB |

|

|

Institutional bldg.

(hospital, govt. or university) |

IB |

|

|

Metal building system |

MBS |

|

|

Service station canopy |

SSC |

|

|

Warehouse (tilt-up

walls or heavy timber) |

WHB |

|

|

Transmission line

tower |

TLT |

|

|

Free-standing tower |

FST |

|

|

Free standing pole

(light, flag, luminary) |

FSP |

|

|

Tree - hardwood |

TH |

|

|

Tree - softwood |

TS |

What is a "significant" tornado? A tornado is classified

as "significant" if it does F2 or greater damage on the Enhanced F

scale. Grazulis (1993) also included

killer tornadoes of any damage scale in his significant tornado database. It is important to know that those

definitions are arbitrary, for scientific research. No tornado is necessarily insignificant. Any tornado can kill or cause damage; and

some tornadoes rated less than F2 probably could do F2 or greater damage if

they hit a well-built house during peak intensity.

How does cloud seeding affect tornadoes? Nobody knows, for

certain. There is no proof that cloud

seeding can or cannot change tornado potential in a thunderstorm. This is because there is no way to know that

the things a thunderstorm does after seeding would not have happened anyway. This includes any presence or lack of rain,

hail, wind gusts or tornadoes. Because

the effects of seeding are impossible to prove or disprove, there is a great

deal of controversy in meteorology about whether it works, and if so, under

what conditions, and to what extent.

What does a tornado sound like? That depends on what it is hitting, its

size, intensity, closeness and other factors.

The most common tornado sound is a continuous rumble, like a close by

train. Sometimes a tornado produces a

loud whooshing sound, like that of a waterfall or of open car windows while

driving very fast. Tornadoes, which are

tearing through densely populated areas, may be producing all kinds of loud

noises at once, which collectively may make a tremendous roar. Just because you may have heard a loud roar

during a damaging storm does not necessarily mean it was a tornado. Any intense thunderstorm wind can produce

damage and cause a roar.

Do hurricanes and tropical storms produce tornadoes? There are great

differences from storm to storm, not necessarily related to tropical cyclone

size or intensity. Some land falling

hurricanes in the U.S. fail to produce any known tornadoes, while others cause

major outbreaks. The same hurricane

also may have none for a while, then erupt with tornadoes...or vice versa. Andrew (1992), for example, spawned several

tornadoes across the Deep South after crossing the Gulf, but produced none

during its rampage across South Florida. Katrina (2005) spawned numerous

tornadoes after its devastating LA/MS landfall, but only one in Florida (in the

Keys). Though fewer tornadoes tend to

occur with tropical depressions and tropical storms than hurricanes, there are

notable exceptions like TS Beryl of 1994 in the Carolinas. Some tropical cyclones even produce two

distinct sets of tornadoes -- one around the time of landfall over Florida or

the Gulf Coast, the other when well inland or exiting the Atlantic coast.

Counter Measure Against Tornadoes (CMAT): Can't we weaken or

destroy tornadoes somehow, like by bombing them or sucking out their heat with

a bunch of dry ice? The main problem

with anything, which could realistically stand a chance at affecting a tornado,

is that it would be even more deadly and destructive than the tornado itself.

Lesser things (like huge piles of dry ice or smaller conventional weaponry)

would be too hard to deploy in the right place fast enough, and would likely

not have enough impact to affect the tornado much anyway. Imagine the legal problems one would face,

too, by trying to bomb or ice a tornado, then inadvertently hurting someone or

destroying private property in the process.

In short -- bad idea!

Classification Occurrence: In the United States, 75 percent of the

tornadoes rate F0 or F1 in strength.

Most remaining tornadoes rate F2 or F3, with only 1 percent rating F4 or

F5. Usually no more than one or two

tornadoes per year reach F5 strength.

On the other hand, the few F4 and F5 tornadoes account for 67 percent of

the fatalities caused by tornadoes.

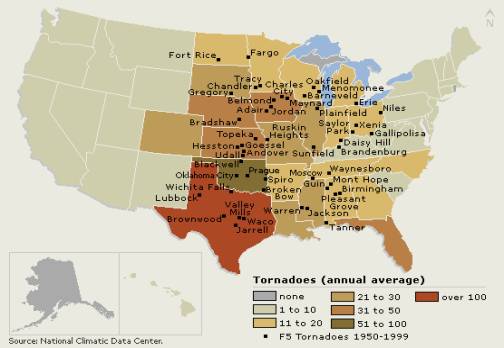

Geography of Tornado Occurrence: The annual average occurrence of tornadoes in

the United States by state and sites of the biggest tornadoes in the period

from 1950 to 1999 are depicted below.

Most tornadoes occur in the central part of the country, in an area known

as Tornado Alley. Even in tornado alley, a twister hits a given square mile only

once every 700 years, Wolfe adds, "It's not economically feasible to build

a house to resist that kind of wind.

That's why you get insurance."

© Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 3 -

Tornado Locations and Frequency

The United States has the highest

average annual number of tornadoes in the world, about 800 per year. Outside the United States, Australia ranks

second in tornado frequency. Tornadoes

also occur in many other countries, including China, India, Russia, England,

and Germany. Bangladesh has been struck several times by devastating killer

tornadoes.

In the United States, tornadoes occur in all 50 states. However, the region with the most tornadoes

is “Tornado Alley,” a swath of the Midwest extending from the Texas Gulf

Coastal Plain northward through eastern South Dakota. Another area of high concentration is “Dixie Alley,” which

extends across the Gulf Coastal Plain from south Texas eastward to

Florida. Tornadoes are most frequent in

the Midwest, where conditions are most favorable for the development of the

severe thunderstorms that produce tornadoes.

The Gulf of Mexico ensures a supply of moist, warm air that enables the

storms to survive. Weather conditions

that trigger severe thunderstorms are frequently in place here: convergence

(flowing together) of air along boundaries between dry and moist air masses,

convergence of air along the boundaries between warm and cold air masses, and

low pressure systems in the upper atmosphere traveling eastward across the

plains.

In winter, tornado activity is usually confined to the Gulf

Coastal Plain. In spring, the most

active tornado season, tornadoes typically occur in central Tornado Alley and

eastward into the Ohio Valley. In

summer, most tornadoes occur in a northern band stretching from the Dakotas

eastward into Pennsylvania and southern New York State.

The worst tornado disasters in the United States have claimed

hundreds of lives. The Tri-State

Outbreak of March 18, 1925, had the highest death toll: 740 people died in 7

tornadoes that struck Illinois, Missouri, and Indiana. The Super Outbreak of April 3-4, 1974,

spawned 148 tornadoes (the most in any known outbreak) and killed 315 people

from Alabama north to Ohio.

Protection Against Tornadoes

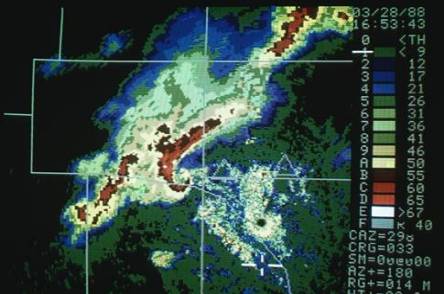

The Doppler Radar: The Image Doppler radar measures the speed

and direction of the movement of clouds, in addition to cloud density. The image depicted below is a thunderstorm

over Oklahoma, Doppler radar shows a mesocyclone, a rotating mass of air that

may signal that the formation of a tornado is imminent.

Bruce Coleman, Inc./Phil Designer

Figure 4 -

Doppler Radar Image, Bruce Coleman, Inc./Phil Degginger

The National

Weather Service alerts the public to severe weather hazards by issuing watches

and warnings that are broadcast on National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration (NOAA) weather radio, television, and commercial radio. Meteorologists issue a tornado watch when

weather conditions are favorable for the development of tornadoes and severe

thunderstorms. Watches are often issued

hours before severe weather develops and generally cover many counties or even

several states.

Tornado Watch : Issued by the National

Weather Service when weather conditions are ripe for tornadoes. Remind your family where to find

shelter. Turn on a radio or television

and listen for announcements. Since

tornado prediction is an inexact science, you may get little warning of an

actual funnel cloud.

Tornado Warning: A tornado warning means that a tornado is

occurring or is imminent. A warning is

issued if a tornado has touched down, if a funnel cloud is present, or if

Doppler radar indicates the presence of strong rotation in a thunderstorm updraft. The area covered by a warning is much

smaller than a watch, usually only a county or two, or a portion of a county.

Precautions: During a tornado warning, people should seek shelter immediately

in a basement or in the interior portion of a building (a closet, interior

hallway, or bathroom). Mobile homes and cars have a tendency to roll in high

winds and should therefore be abandoned.

Structures with large, free-span roofs, such as auditoriums, gymnasiums,

and supermarkets, are subject to collapse and should also be avoided. If caught outside, a person should lie flat

in a ditch and cover his or her head for protection from flying debris.

What is a safe room? So-called "safe rooms" are

reinforced small rooms built in the interior of a home, which are fortified by

concrete and/or steel to offer extra protection against tornadoes, hurricanes

and other severe windstorms. They can

be built in a basement, or if no basement is available, on the ground

floor. In existing homes, interior

bathrooms or closets can be fortified into "safe rooms" also.

What were the deadliest U.S. tornadoes? The

"Tri-state" tornado of 18 March 1925 killed 695 people as it raced

along at 60-73 mph in a 219-mile long track across parts of Missouri, Illinois

and Indiana, producing F5 damage. The

death toll is an estimate based on the work of Grazulis (1993); older

references have different counts. This

event also holds the known record for most tornado fatalities in a single city

or town: at least 234 at Murphysboro IL.

The 25 deadliest tornadoes on record are listed here. We also have web links related to this and

other major tornado events.

What were the deadliest U.S. tornado days? On 3 April

1974, the main day of the two-day "Super Outbreak," tornadoes killed

308 people. The next deadliest day for

tornadoes was 11 April 1965, the original "Palm Sunday Outbreak,"

where 260 perished. A list is online of top 20 deadliest tornado days since

detailed record keeping began in 1950.

The biggest known tornado (the Hallam, Nebraska F4 tornado) of 22

May 2004 is the newest record-holder for peak width, at nearly two and a half

miles, as surveyed by Brian Smith of NWS Omaha. This is probably close to the maximum size for tornadoes, but it

is possible that larger, unrecorded ones have occurred.

A single month had the most tornadoes. The record for most tornadoes in any month (since modern tornado

record keeping began in 1950) was set in May 2003, with 543 tornadoes confirmed

in the final numbers. This easily broke

the old mark of 399, set in June 1992.

Tornado Season: Tornado season usually means the peak period for historical

tornado reports in an area, when averaged over the history of reports. There is a general northward shift in "tornado

season" in the U.S. from late winter through mid summer. The peak period

for tornadoes in the southern plains, for example, is during May into early

June. On the Gulf coast, it is earlier

during the spring; in the northern plains and upper Midwest, it is June or

July.

The Highest-Elevation Tornado: Do they happen in the mountains West? The highest elevation a tornado has ever

occurred is unknown; but it is at least 10,000 feet above sea level. On 7 July 2004, a hiker observed and

photographed a tornado at 12,000 feet in Sequoia National Park,

California. That probably was the

highest elevation tornado observed in the U.S.

On 21 July 1987, there was a violent (F4 damage) tornado in Wyoming

between 8,500 and 10,000 feet in elevation, the highest altitude ever recorded

for a violent tornado. There was F3

damage from a tornado at up to 10,800 ft elevation in the Unita Mountains of

Utah on 11 August 1993.

While not so lofty in elevation, the Salt Lake City tornado of 11

August 1999 produced F2 damage. On

August 31, 2000, a super cell spawned a photogenic tornado in Nevada. Tornadoes

are generally a lot less frequent west of the Rockies per unit area with a

couple of exceptions. One exception is

the Los Angeles Basin, where weak-tornado frequency over tens of square miles

is on par with that in the Great Plains. Elsewhere, there are probably more

high-elevation Western tornadoes occurring than we have known about, just

because many areas are so sparsely populated, and they lack the density of

spotters and storm chasers as in the Plains.

The probability of a tornado near my house. The frequency that a

tornado can hit any particular square mile of land is about every thousand

years on average -- but it varies around the country. The reason this is not an exact number is because we don't have a

long and accurate enough record of tornadoes to make more certain

(statistically sound) calculations. The

probability of any tornado hitting within sight of a spot (let's say 25

nautical miles) also varies during the year and across the country. Detailed maps so you can judge the tornado

probabilities within 25 miles of your location have been engineered by Dr.

Harold Brooks of NSSL. He has used

statistical extensions of 1980-1994 tornado data, believed to be the most

representative to prepare many kinds of threat maps and animations.

The difference between a funnel cloud and a tornado. What is a funnel

cloud? In a tornado, a damaging

circulation is on the ground -- whether or not the cloud is. A true funnel cloud rotates, but has no

ground contact or debris, and is not doing damage. If it is a low-hanging cloud with no rotation, it is not a funnel

cloud. Caution: tornadoes can happen

without a funnel; and what looks like "only" a funnel cloud may be

doing damage, which can't be seen from a distance. Some funnels are high-based and may never touch down. Still, since a funnel cloud might quickly

become a tornado (remember rotation), it should be reported by spotters.

Some tornadoes are white, and others black or gray or even red: Tornadoes tend to look

darkest when looking southwest through northwest in the afternoon. In those cases, they are often silhouetted

in front of a light source, such as brighter skies west of the

thunderstorm. If there is heavy

precipitation behind the tornado, it may be dark gray, blue or even white --

depending on where most of the daylight is coming from. This happens often when the spotter is

looking north or east at a tornado, and part of the forward-flank and/or

rear-flank cores. Tornadoes wrapped in

rain may exhibit varieties of gray shades on gray, if they are visible at

all. Lower parts of tornadoes also can

assume the color of the dust and debris they are generating; for example, a

tornado passing across dry fields in western or central Oklahoma may take on

the hue of the red soil so prevalent there.

North America has the ingredients of a tornado. To understand this

phenomenon, consider the basic ingredients of a thunderstorm: warm, moist air

near the ground; dry air aloft (between altitudes of about three and 10

kilometers) and some mechanism such as a boundary between two air masses to

lift the warm, moist air upwards.

Storms that produce strong tornadoes are also most likely to occur when

the horizontal winds in the environment increase in speed and change with

increasing altitude. In the most common

directional change of this kind, the surface winds blow from the equator-ward

direction at the surface and out of the west a few kilometers above the

ground. When this wind pattern occurs

in the central part of the U.S., the surface winds come from the direction of

the Gulf of Mexico, bringing in warm, moist air at the surface, and the winds

aloft come from over the Rocky Mountains and are relatively dry. (Lifting air and heating it over a wide,

high range of mountains is an ideal way to dry it.) As a result, when the winds over the central part of the U.S are

correct for making thunderstorms, they often bring together the right

combination of the vertical temperature and moisture profile most likely to

produce tornadoes.

No other part of the world has the combination of a warm, moist

air source on the equator ward side and a wide, high range of mountains to the

west that extends for thousands of kilometers from north to south that provides

the right atmospheric conditions for frequent tornadoes. The Andes Mountains are not as wide as the

Rockies, and the Himalayas don’t extend as far north and south. Typically, air coming onshore off the Gulf

has spent a longer time over the warm water than air coming onshore off of the

Mediterranean Sea and is moister as a result.

The Drakensberg Plateau in South Africa is not as high as the

Rockies. In summary, other regions of

the world that occasionally get strong tornadoes don’t experience the

combination of all the necessary tornado elements as often as the central U.S.

does.

Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma are prone to tornadoes. The central part of the

U.S. gets many tornadoes, particularly strong and violent ones, because of the

unique geography of North America. The

combination of the Gulf of Mexico to the south and the Rocky Mountains to the

west provides ideal environmental conditions for the development of tornadoes

more often there than any other place on earth.

Damage from tornadoes compared to that of hurricanes. The differences are in

scale. Even though winds from the strongest tornadoes far exceed that from the

strongest hurricanes, hurricanes typically cause much more damage individually

and over a season, and over far bigger areas.

Economically, tornadoes cause about a tenth as much damage per year, on

average, as hurricanes. Hurricanes tend

to cause much more overall destruction than tornadoes because of their much

larger size, longer duration and their greater variety of ways to damage

property. The destructive core in hurricanes

can be tens of miles across, last many hours and damage structures through

storm surge and rainfall-caused flooding, as well as from wind. Tornadoes, in contrast, tend to be a few

hundred yards in diameter, last for minutes and primarily cause damage from

their extreme winds.

The Costliest Tornado: A tornado in central and northern Georgia,

on 31 March 1973, is listed in Storm Data as having produced $1,250,000,000.00

in actual damage and $5,175,000,000.00 when inflation-adjusted -- both record amounts. The Bridge Creek-Moore-Oklahoma City-Midwest

City, OK, tornado of 3 May 1999 currently ranks second in actual dollars but

fourth when inflation adjusted.

Summary: A tornado is "a violently rotating column of air, pendant

from a cumuliform cloud or underneath a cumuliform cloud, and often (but not

always) visible as a funnel cloud."

Super-cell tornadoes are often produced in sequence, so that what

appears to be a very long damage path from one tornado may actually be the

result of a new tornado that forms in the area where the previous tornado

died. The favored location for the

development of a tornado is at the area between this rear-flank downdraft and

the main storm updraft. A tornado

that's 500 meters in diameter looks a lot more ominous than the average

twister, which is "only" 150 meters across.

Gustnado: A gustnado is a small and usually weak whirlwind, which forms as

an eddy in thunderstorm outflows.

"Wedge" tornadoes simply appear to be at least as wide as they

are tall (from ground to ambient cloud base).

"Rope" tornadoes are very narrow, often sinuous or snake-like

in form. There are important

distinctions between satellite and multiple-vortex tornadoes. A satellite tornado develops independently

from the primary tornado -- not inside it, as does a suction vortex.

The energy of a tornado takes many forms, including chemical,

kinetic, potential and thermal. A

tornado with wind speeds of 200 mph releases kinetic energy at the rate of 1

billion watts -- equal to the electric output of a pair of large nuclear

reactors. Tornadoes release a boatload

of energy. A tornado is a type of

vortex -- a spinning column of air with some water vapor. When predicting severe weather (including

tornadoes) a day or two in advance makes a big difference. Tornadoes can appear from any

direction. Rain, wind, lightning, and

hail characteristics vary from storm to storm.

Many tornadoes have been observed to go away soon after being hit by

outflow.

Tornadoes can last from several seconds to more than an hour. A barometer can start dropping many hours or

even days in advance of a tornado if there is low pressure on a broad scale

moving into the area. A waterspout is a

tornado over water -- usually meaning non-super cell tornadoes over water. They rotate cyclonically, which is

counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise south of the

equator. When a tornado doesn't contain

too much dust and debris, they can sometimes be spectacularly visible. A tornado becomes visible when a condensation

funnel made of water vapor (a funnel cloud) forms in extreme low pressures, or

when the tornado lofts dust, dirt, and debris upward from the ground.

The most widely used method worldwide, for over three decades, was

the F-scale developed by Dr. T. Theodore Fujita. In the U.S., and probably elsewhere within a few years, the new

Enhanced F-scale is becoming the standard for assessing tornado damage. Mobile homes present special problems in

tornadoes. New mobile homes must

withstand 30 to 40 percent faster winds, McDonald says (previously, homes were

supposed to survive winds of only 60 mph).

Ninety-five percent of mobile homes are never moved after they are

placed." A tornado is classified

as "significant" if it does F2 or greater damage on the Enhanced F

scale.

There is no proof that cloud seeding can or cannot change tornado

potential in a thunderstorm. The most

common tornado sound is a continuous rumble, like a close by train. There are great differences from storm to

storm, not necessarily related to tropical cyclone size or intensity. Fewer tornadoes tend to occur with tropical

depressions and tropical storms than hurricanes. There are notable exceptions like TS Beryl of 1994 in the

Carolinas. Dry ice has been used as

countermeasure to suck the heat out of tornadoes.

In the United States, 75 percent of the tornadoes rate F0 or F1 in

strength. Most remaining tornadoes rate

F2 or F3, with only 1 percent rating F4 or F5.

Most tornadoes occur in the central part of the country, in an area

known as Tornado Alley. Even in tornado

alley, a twister hits a given square mile only once every 700 years, Wolfe

adds, "It's not economically feasible to build a house to resist that kind

of wind. That's why you get

insurance."

The United States has the highest average annual number of

tornadoes in the world, about 800 per year and occur in all fifty states. Storms that produce strong tornadoes are

also most likely to occur when the horizontal winds in the environment increase

in speed and change with increasing altitude.

The combination of the Gulf of Mexico to the south and the Rocky

Mountains to the west provides ideal environmental conditions for the

development of tornadoes more often there than any other place on earth.

Doppler Radar is being deployed to provide early warning of

tornadoes. The "Tri-state"

tornado of 18 March 1925 killed 695 people as it raced along at 60-73 mph in a

219-mile long track across parts of Missouri, Illinois and Indiana, producing

F5 damage. The Hallam, Nebraska F4

tornado of 22 May 2004 is the newest record-holder for peak width, at nearly

two and a half miles, as surveyed by Brian Smith of NWS Omaha. This is probably close to the maximum size

for tornadoes; but it is possible that larger, unrecorded ones have

occurred. May 2003 set the record of

the most tornadoes. The peak period for

tornadoes in the southern plains, for example, is during May into early June.

On the Gulf coast, it is earlier during the spring; in the

northern plains and upper Midwest, it is June or July. The highest elevation a tornado has ever

occurred is unknown; but it is at least 10,000 feet above sea level. The frequency that a tornado can hit any particular

square mile of land is about every thousand years on average -- but varies

around the country. Economically,

tornadoes cause about a tenth as much damage per year, on average, as

hurricanes. The costliest tornado was

in central and northern Georgia, on 31 March 1973, is listed in Storm Data as

having produced $1,250,000,000.00 in actual damage and $5,175,000,000.00 when

inflation-adjusted -- both record amounts.

Bibliography

Tornadoes, Contributed By: Alan Shapiro, © 1993-2003 Microsoft

Corporation. All rights reserved.

The Tornado Story's Bibliography:

Howard Bluestein, Professor of meteorology, University of Oklahoma

*Hugh Christian, principal investigator, Optical Transient

Detector (OTD)

*Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Ala.

*Robert Davies-Jones, Meteorologist, National Severe Storms

Laboratory, Norman, OK.

*Craig Lorimer, Professor of forestry, University of

Wisconsin-Madison, James McDonald,

Director, Institute for Disaster Research, Professor of Civil Engineering,

Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas

*Ron Wolfe, Research engineer, Forest Products Laboratory,

Madison, Wis.

Note: * Denotes fact checker

A Recommendation for the Enhanced Fujita (EF) Scale, Wind Science

and Engineering Center, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, Contributors: Dr

James R. McDonald and Kishor Mehta, Web Site:www.wind.ttu.edu/F_scale

The Basics about Tornadoes, On Line Tornado (FAQ) by Roger

Edwards, SPC, web site: http://www.spc.noaa.gov/faq/tornado/#References

The Basics about Tornadoes, web site: http://www.spc.noaa.gov/faq/tornado/#the%20Basics

National Severe Storms Laboratory, Severe Thunderstorms

Climatology, Dr. Dusan Srnic, web site: http://www.nssl.noaa.gov/hazard/

Eye of the Storm: Inside the World's Deadliest Hurricanes,

Tornadoes, and Blizzards Book by

Jeffrey O. Rosenfeld; Plenum Press, 1999 ,Subjects: Blizzards, Hurricanes,

Tornadoes, The World's Largest Online Library, web site:

http://www.questia.com/SM.qst

Tornado History and Climatology

Concannon, P.R., H.E. Brooks and C.A. Doswell III, 2000:

Climatological risk of strong and Violent Tornadoes in the United States. Reprints, 2nd Conf. Environ. Applications,

American Meteor. Soc., Long Beach, CA.

Brooks, H.E., C. A. Doswell III, and M. P. Kay, 2003:

Climatological estimates of local daily tornado probability for the United

States. Weather Forecasting, 18, 626–640.

What makes Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma prone to tornadoes, by T.

Irwin, Kissimmee, Florida-originally published August 11, 2003.

General Note:

Important note about enhanced F-Scale winds: The enhanced F-Scale

is a set of wind estimates (not measurements) based on damage. It uses three-second gusts estimated at the

point of damage based on a judgment of 8 levels of damage to 28 indicators. These estimates vary with height and

exposure. Important: The 3-second gust is not the same wind as

standard surface observations. Standard

measurements are taken by weather stations in open exposures, using a directly

measured and “one minute mile" speed.