Union General Ulysses S. Grant Report

By Dr. Frank J. Collazo

December 27, 2006

Ulysses S. Grant, the Union Army’s greatest general, led his troops to victory in the American Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln selected Grant to lead the Union forces on March 9, 1864, following a string of unsuccessful commanders

Introduction:

Late in the administration of Andrew Johnson, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

quarreled with the President and aligned himself with the Radical

Republicans. He was, as the symbol of

the Union victory during the Civil War, their logical candidate for President

in 1868.

When he was elected, the American people hoped for an end to

turmoil. Grant provided neither vigor

nor reform. Looking to Congress for

direction, he seemed bewildered. One

visitor to the White House noted "a puzzled pathos, as of a man with a

problem before him of which he does not understand the terms."

Born in 1822, Grant was the son of an Ohio tanner. He went to West Point rather against his

will and graduated in the middle of his class.

In the Mexican War he fought under General Zachary Taylor.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Grant was working in his

father's leather store in Galena, Illinois.

He was appointed by the Governor to command an unruly volunteer

regiment. Grant whipped it into shape,

and by September 1861 he had risen to the rank of brigadier general of

volunteers.

He sought to win control of the Mississippi Valley. In February 1862 he took Fort Henry and

attacked Fort Donelson. When the

Confederate commander asked for terms, Grant replied, "No terms except an

unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted." The Confederates

surrendered, and President Lincoln promoted Grant to major general of

volunteers.

At Shiloh in April, Grant fought one of the bloodiest battles in

the West and came out less well.

President Lincoln fended off demands for his removal by saying, "I

can't spare this man--he fights."

For his next major objective, Grant maneuvered and fought skillfully to

win Vicksburg, the key city on the Mississippi, and thus cut the Confederacy in

two. Then he broke the Confederate hold

on Chattanooga.

Lincoln appointed him General-in-Chief in March 1864. Grant directed Sherman to drive through the

South while he himself, with the Army of the Potomac, pinned down General

Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

Finally, on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Lee

surrendered. Grant wrote out

magnanimous terms of surrender that would prevent treason trials.

As President, Grant presided over the Government much as he had

run the Army. Indeed he brought part of

his Army staff to the White House.

Although a man of scrupulous honesty, Grant as President accepted

handsome presents from admirers. Worse,

he allowed himself to be seen with two speculators, Jay Gould and James

Fisk. When Grant realized their scheme

to corner the market in gold, he authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to

sell enough gold to wreck their plans, but the speculation had already wrought

havoc with business.

During his campaign for re-election in 1872, Liberal Republican

reformers attacked Grant. He called

them "narrow-headed men," their eyes so close together that

"they can look out of the same gimlet hole without winking." The General's friends in the Republican

Party came to be known proudly as "the Old Guard."

Grant allowed Radical Reconstruction to run its course in the South,

bolstering it at times with military force.

After retiring from the Presidency, Grant became a partner in a

financial firm, which went bankrupt.

About that time he learned that he had cancer of the throat. He started writing his recollections to pay

off his debts and provide for his family, racing against death to produce a

memoir that ultimately earned nearly $450,000.

Soon after completing the last page, in 1885, he died.

After service in the Mexican War, an undistinguished peacetime

military career, and a series of unsuccessful civilian jobs, Grant proved

highly successful in training new recruits in 1861. His capture of Fort Henry

and Fort Donelson

in February 1862 marked the first major Union victories of the civil war and

opened up prime avenues of invasion to the South. Surprised and nearly defeated at Shiloh (April 1862), he fought back and took

control of most of western Kentucky and Tennessee.

His great achievement in 1862-63 was to seize control of the Mississippi River by defeating a series of

uncoordinated Confederate

armies and by capturing Vicksburg in

July 1863. After a victory at Chattanooga

in late 1863, Abraham Lincoln

made him general-in-chief of all Union armies.

Grant was the first Union general to initiate

coordinated offensives across multiple theaters in the war. While his subordinates Sherman and Sheridan

marched through Georgia

and the Shenandoah Valley,

Grant personally supervised the 1864 Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee's Army in Virginia. He employed a war of attrition against his opponent,

conducting a series of large-scale battles with very high casualties that

alarmed public opinion, while maneuvering ever closer to the Confederate

capital, Richmond. Grant announced he would "fight it out

on this line if it takes all summer."

Lincoln supported his general and replaced his losses, but Lee's

dwindling army was forced into defending trenches around Richmond and Petersburg.

In April 1865 Grant's vastly larger army

broke through, captured Richmond, and forced Lee to surrender at Appomattox. Military historians usually place Grant in the

top ranks of great generals. He has

been described by J.F.C. Fuller as

"the greatest general of his age and one of the greatest strategists of

any age." His Vicksburg Campaign

in particular is scrutinized by military specialists around the world.

Grant announced generous terms for his defeated foes, and pursued a policy

of peace. He broke with President Andrew Johnson in 1867 and was elected President

as a Republican

in 1868. He led Radical Reconstruction

and built a powerful patronage-based Republican party in the South, with the

adroit use of the army. He took a hard

line that reduced violence by groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

Grant was personally honest, but he not only tolerated financial and

political corruption among top aides, he protected them once exposed. He blocked civil service reforms and defeated the reform

movement in the Republican party in 1872, driving out many of its

founders.

The Panic of 1873 pushed

the nation into a depression

that Grant was helpless to reverse. Presidential experts typically rank Grant in the lowest

quartile of U.S. presidents, primarily for his tolerance of corruption. In recent years, however, his reputation as

president has improved somewhat among scholars impressed by his support for civil rights for African Americans. Unsuccessful in winning a third term in

1880, bankrupted by bad investments, and terminally ill with throat cancer,

Grant wrote his Memoirs which were enormously successful among veterans,

the public, and the critics.

Birth and early years

Ulysses S.

Grant Boyhood Home, Georgetown, Ohio

Born

Hiram Ulysses Grant in Point Pleasant

(Log Cabin), Clermont County,

Ohio,

25 miles (40 km) east of Cincinnati on the Ohio River, he was the eldest of the six

children of Jesse Root Grant (1794–1873) and Hannah Simpson (1798–1883). His father, a tanner, and his mother were

born in Pennsylvania.

In the fall of 1823, they moved to the village of Georgetown in Brown County, Ohio,

where Grant spent most of his time until he was 17.

At the

age of 17, and having barely passed the United States

Military Academy's height requirement for entrance, Grant received a

nomination to the Academy at West Point, New York,

through his U.S. Congressman,

Thomas L. Hamer. Hamer erroneously nominated him as Ulysses Simpson Grant, knowing

Grant's mother's maiden name and forgetting that Grant was referred to in his

youth as "H. Ulysses Grant" or "Lyss."

Grant

wrote his name in the entrance register as "Ulysses Hiram Grant"

(concerned that he would otherwise become known by his initials, H.U.G.) but

the school administration refused to accept any name other than the nominated

form. Upon graduation, Grant adopted

the form of his new name with middle initial only, never acknowledging that the

"S" stood for Simpson. He

graduated from West Point in 1843, ranking 21st in a class of 39. At the academy, he established a reputation

as a fearless and expert horseman.

Grant drank whiskey and, during the Civil War, began smoking huge

numbers of cigars (one story had it that he smoked over 10,000 in five years)

which may well have contributed to the development of throat cancer later in

his life.

On August 22, 1848

Grant married Julia Boggs Dent

(1826–1902), the daughter of a slaveowner.

They had four children: Frederick Dent Grant,

Ulysses S.

(Buck) Grant, Jr., Ellen (Nellie)

Wrenshall Grant, and Jesse Root Grant.

West Point Cadet Predicted General Grant's Future: A few months before

graduation, one of Grant's classmates, James A. Hardie, said to his friend and

instructor, "Well, sir, if a great emergency arises in this country during

our life-time, Sam Grant will be the man to meet it." If I had heard Hardie's prediction I doubt

not I should have believed in it, for I thought the young man who could perform

the feat of horsemanship I had witnessed, and wore a sword, could do anything.

I was in General Grant's room in New York City on the 25th of May

1885. Forty years had elapsed since

Hardie's prediction was made, and it had been amply fulfilled. But, alas, the hand of death was upon the

hero of it. Though brave and cheerful,

he was almost voiceless. Before him

were sheets of his forthcoming book, and a few artists’ proofs of a steel

engraving of himself made from a daguerreotype taken soon after his

graduation. He wrote my name and his

own upon one of the engravings and handed it to me.

I said, "General, this looks as you did the first time I ever

saw you. It as when you made the great

jump in the riding exercises of your graduation. Yes,” he whispered, "I remember that very well. York was a wonderful horse. I could feel him gathering under me for the

effort as he approached the bar. Have

you heard anything lately of Hershberger?"

I replied, "No, I never heard of him after he left West Point

years ago. Oh," said the general,

"I have heard of him since the war.

He was in Carlisle, old and poor, and I sent him a check for fifty

dollars." This early friendship

had lived for forty years, and the old master was enabled to say near the close

of his pupil's career, as he had said at the beginning of it, "Very well

done, sir!"

Military Career

Grant at the capture of the city of Mexico, painting by

Emanuel Leutze.

Mexican War: Grant served in the Mexican-American War

(1846–1848) under Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, taking part in the battles of Resaca de la

Palma, Palo Alto, Monterrey, and

Veracruz. He was twice brevetted for

bravery: at Molino del Rey

and Chapultepec.

Between Wars:

After the Mexican war ended in 1848, Grant remained in the army and was

moved to several different posts. He

was sent to Fort Vancouver in

the Washington Territory

in 1853, where he served as regimental quartermaster of the 4th U.S. Infantry

regiment. His wife could not

accompany him because his salary could not support a family (she was eight

months pregnant with their second child) on the frontier.

In 1854,

he was promoted to captain and assigned to command Company F, 4th Infantry, at Fort

Humboldt, California.

Despite the increase in pay, he still could not afford to bring his

family out West. He tried some business ventures while in California to supplement

his income, but they failed. He started

drinking heavily because of money woes and missing his wife. Because his drinking was having an effect on

his military duties, he was given a choice by his superiors: resign his

commission or face trial. He resigned

on July 31, 1854. Seven years of civilian life followed, in

which he was a farmer and a real estate agent in St. Louis, Missouri,

where he owned one slave (whom he let go free) a bill collector and finally an

assistant in the leather shop owned by his father and brother in Galena, Illinois. The land and cabin where Grant lived in St. Louis is now an

animal conservation reserve, Grant's Farm, owned and operated by the Anheuser-Busch Company.

Grant

was nonpolitical, but in 1856 he voted for Democrat James Buchanan for president to avert secession

and because "I knew Frémont" (the Republican candidate). In 1860, he favored Democrat Stephen A. Douglas

but did not vote. In 1864, he allowed

his political sponsor, Congressman Elihu B. Washburne,

to use his private letters as campaign literature for the Union Party, which

combined both Republicans and War Democrats.

He refused to announce his politics until 1868, when he finally declared

himself a Republican.

Western Theater: 1861–63

The home of President Grant while he lived in Galena, Illinois.

Shortly

after Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter, President

Abraham Lincoln put out a call for 75,000

volunteers. Grant helped recruit a

company of volunteers, and despite declining the unit's captaincy, he

accompanied it to Springfield,

the capital of Illinois.

Grant accepted a position offered by Illinois Governor Richard Yates

to recruit volunteers, but he pressed for a field command on multiple

occasions. The governor, recognizing

that Grant was a West Point graduate, eventually appointed him Colonel of the undisciplined and rebellious 21st

Illinois Infantry, effective June 17, 1861.

Although

part of the Illinois militia, Grant was deployed to Missouri protect the Hannibal and

St. Joseph Railroad from attacks that would interrupt the Pony Express mail service. At the time Missouri

under Governor Claiborne Jackson

had declared it was an armed neutral in the conflict and would attack troops

from either side entering the state. By the first of August the Union army had

forcibly removed Jackson, and Missouri was formally a Union state -- although a

state with many southern sympathizers.

On August 7, Grant was appointed brigadier general of volunteers, a decision by

President Lincoln that was strongly influenced by Elihu Washburne's political

clout. After first serving in a couple of lesser commands, at the end of the

month, Grant was selected by Western Theater commander Major General John C. Frémont to command the critical District

of Southeast Missouri.

Battles of Belmont, Henry, and Donelson: Grant's first important strategic act of the

war was to take the initiative to seize the Ohio River town of Paducah, Kentucky,

immediately after the Confederates

violated the state's neutrality by occupying Columbus, Kentucky. He fought his first battle, an indecisive

action against Confederate General Gideon J. Pillow at Belmont, Missouri, in November 1861. Three months later, aided by Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote's gunboats, he captured Fort Henry on

the Tennessee River

and Fort Donelson

on the Cumberland River. At Donelson, his army was hit by a surprise

Confederate attack (once again by Pillow) while he was temporarily absent. Displaying the cool determination that would

characterize his leadership in future battles, he organized counterattacks that

carried the day.

The

captures of the two forts were the first major Union victories of the war. The Confederate commander, Brigadier General Simon B. Buckner,

an old friend of Grant's, yielded to Grant's hard conditions of "no terms

except unconditional and immediate surrender." Buckner's surrender of 14,000 men made Grant a national figure

almost overnight, and he was nicknamed "Unconditional Surrender"

Grant. This victory also won him

promotion to major general of volunteers.

Despite

his significant victories, or perhaps because of them, Grant fell out of favor

with his superior, Major General Henry W. Halleck. Halleck objected to Grant's visit to Nashville, Tennessee,

where he met with Halleck's rival, Don Carlos Buell, and used that as an excuse to

relieve Grant of field command on March 2. Personal intervention from President Lincoln

caused Halleck to restore Grant, who rejoined his army on March 17.

Shiloh

General Grant at Cold Harbor,

photographed by Mathew Brady in 1864.

In early

April 1862, Grant was surprised by Generals Albert Sidney Johnston

and P.G.T. Beauregard

at the Battle of Shiloh. The sheer violence of the Confederate attack

sent the Union forces reeling.

Nevertheless, Grant refused to retreat.

With grim determination, he stabilized his line. Then, on the second day, with the help of

timely reinforcements, Grant counterattacked and turned a serious reverse into

a victory.

The victory at Shiloh came at a high price; it was the bloodiest battle in

the history of the United States up to that time with over 23,000

casualties. Halleck responded to the

surprise and the disorganized nature of the fighting by taking command of the

army in the field himself on April 30, relegating

Grant to the powerless position of second-in-command for the campaign in Corinth, Mississippi. Despondent over this reversal, Grant decided

to resign. The intervention of his

subordinate and good friend, William T. Sherman,

caused him to remain. When Halleck was

promoted to general-in-chief of the Union Army, Grant resumed his position as

commander of the Army of West Tennessee

(later more famously named the Army of the Tennessee)

on June 10.

He commanded the army for the battles of Corinth

and Iuka that fall.

Vicksburg: In

the campaign to capture the Mississippi River fortress of Vicksburg, Mississippi,

Grant spent the winter of 1862–1863 conducting a series of operations to gain

access to the city through the region's bayous. These attempts failed.

His strategy in the campaign to capture Vicksburg in 1863 is considered

one of the most masterful in military history.

Grant

marched his troops down the west bank of the Mississippi and crossed the river

by using the U.S. Navy ships that had run the guns at

Vicksburg. There, he moved inland

and—in a daring move that defied conventional military principles—cut loose

from most of his supply lines. Operating

in enemy territory, Grant moved swiftly, never giving the Confederates, under

the command of John C. Pemberton,

an opportunity to concentrate their forces against him. Grant's army went eastward, captured the

city of Jackson, Mississippi,

and severed the rail line to Vicksburg.

Knowing that the Confederates could no longer send reinforcements to the

Vicksburg garrison, Grant turned west and won at Champion Hill. The defeated Confederates retreated inside

their fortifications at Vicksburg, and Grant promptly surrounded the city.

Finding that assaults against the impregnable breastworks were futile, he

settled in for a six-week siege. Cut off and with no possibility of relief,

Pemberton surrendered to Grant on July 4, 1863. It was a devastating defeat for the Southern

cause, effectively splitting the Confederacy in two, and, in conjunction with

the Union victory at Gettysburg

the previous day, is widely considered the turning

point of the war. For this

victory, President Lincoln promoted Grant to the rank of major general in the

regular army, effective July 4.

Chattanooga: After

the Battle of Chickamauga

Union General William S. Rosecrans

retreated to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Confederate Braxton Bragg followed to Lookout Mountain, surrounding the Federals on

three sides. On October 17, Grant was placed in command of the

city. He immediately relieved Rosecrans

and replaced him with George H. Thomas. Devising a plan known as the "Cracker

Line," Grant's chief engineer, William F.

"Baldy" Smith, opened a new supply route to Chattanooga,

greatly increasing the chances for Grant's forces.

Upon

reprovisioning and reinforcing, the morale of Union troops lifted. In late November, they went on the

offensive. The Battle of

Chattanooga started out with Sherman's failed attack on the

Confederate right. He not only attacked

the wrong mountain but committed his troops piecemeal, allowing them to be

defeated by one Confederate division. In

response, Grant ordered Thomas to launch a demonstration on the center, which

could draw defenders away from Sherman.

Thomas waited until he was certain that Hooker, with reinforcements from

the Army of the Potomac, was engaged on the Confederate left before he launched

the Army of the Cumberland at the center of the Confederate line.

Hooker's

men broke the Confederate left, while Thomas's men made an unexpected but

spectacular charge straight up Missionary Ridge and broke the fortified center

of the Confederate line. Grant was

initially angry at Thomas that his orders for a demonstration were exceeded,

but the assaulting wave sent the Confederates into a head-long retreat, opening

the way for the Union to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the

Confederacy.

Grant's willingness to fight and ability to win impressed President

Lincoln, who appointed him lieutenant general

in the regular army—a new rank recently authorized by the U.S. Congress

with Grant in mind—on March 2, 1864. On March 12, Grant became general-in-chief of all

the armies of the United States.

General-in-Chief and strategy for victory

Statue

of Grant astride his favorite mount, "Cincinnati", at Vicksburg,

Mississippi

In March

1864, Grant put Major General William Tecumseh

Sherman in immediate command of all forces in the West and moved his

headquarters to Virginia where he turned his attention to the

long-frustrated Union effort to destroy the Army of Northern

Virginia.

His

secondary objective was to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia,

but Grant knew that the latter would happen automatically once the former was

accomplished. He devised a coordinated

strategy that would strike at the heart of the Confederacy from multiple

directions: Grant, George G. Meade, and

Benjamin

Franklin Butler against Lee near Richmond; Franz Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley; Sherman to invade Georgia,

defeat Joseph E. Johnston,

and capture Atlanta; George Crook and William W. Averell

to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; and Nathaniel Banks

to capture Mobile, Alabama.

Grant

was the first general to attempt such a coordinated strategy in the war and the

first to understand the concepts of total war, in which the destruction of an

enemy's economic infrastructure that supplied its armies was as important as

tactical victories on the battlefield.

Overland Campaign,

Petersburg, and Appomattox

Poster of "Grant from West Point to

Appomattox."

The Overland Campaign was the military thrust needed

by the Union to defeat the Confederacy.

It pitted Grant against the great commander Robert E. Lee in an epic contest. It began on May 4, 1864, when the Army of the Potomac

crossed the Rapidan River,

marching into an area of scrubby undergrowth and second growth trees known as

the Wilderness. It was such difficult

terrain that the Army of Northern

Virginia was able to use it to prevent Grant from fully exploiting

his numerical advantage.

The Battle of the

Wilderness was a stubborn, bloody two-day fight, resulting in

advantage to neither side, but with heavy casualties on both. After similar battles in Virginia against

Lee, all of Grant's predecessors had retreated from the field. Grant ignored the setback and ordered an

advance around Lee's flank to the southeast, which lifted the morale of his

army. Grant's strategy was not to win

individual battles, it was to wear down and destroy Lee's army.

Sigel's

Shenandoah campaign and Butler's James River campaign both failed. Lee was able to reinforce with troops used

to defend against these assaults. The

campaign continued, but Lee, anticipating Grant's move, beat him to Spotsylvania, Virginia,

where, on May 8, the fighting resumed. The Battle of

Spotsylvania Court House lasted 14 days. On May 11, Grant wrote a famous dispatch containing

the line "I propose to fight it out along this line if it takes all

summer." These words summed up his

attitude about the fighting, and the next day, May 12, he ordered a massive assault that nearly

broke Lee's lines.

In spite

of mounting Union casualties, the contest's dynamics changed in Grant's favor.

Most of Lee's great victories in earlier years had been won on the offensive,

employing surprise movements and fierce assaults. Now, he was forced to continually fight on the defensive. The next major battle, however, demonstrated

the power of a well-prepared defense.

Cold Harbor

was one of Grant's most controversial battles, in which he launched on June 3 a massive three-corps assault without

adequate reconnaissance on a well-fortified defensive line, resulting in

horrific casualties (3,000–7,000 killed, wounded, and missing in the first 40

minutes. Although modern estimates have

determined that the total was likely less than half of the famous figure of

7,000 that has been used in books for decades, as many as 12,000 casualties for

the day far outnumbered the Confederate losses.

The

normally imperturbable general was observed crying as the magnitude of the

slaughter became known. Grant said of

the battle in his memoirs "I have always regretted that the last assault

at Cold Harbor was ever made. I might

say the same thing of the assault of the 22nd of May, 1863, at Vicksburg. At Cold Harbor no advantage whatever was

gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained." But Grant moved on and kept up the pressure. He stole a march on Lee, slipping his troops

across the James River.

Arriving

at Petersburg, Virginia,

first, Grant should have captured the rail junction city, but he failed because

of the overly cautious actions of his subordinate William Smith. Over the next

three days, a number of Union assaults to take the city were launched. But all failed, and finally on June 18, Lee's veterans arrived. Faced with fully manned trenches in his

front, Grant was left with no alternative but to settle down to a siege.

As the

summer drew on and with Grant's and Sherman's

armies stalled, respectively in Virginia and Georgia, politics took center

stage. There was a presidential

election in the fall, and the citizens of the North had difficulty seeing any

progress in the war effort. To make

matters worse for Abraham Lincoln,

Lee detached a small army under the command of Major General Jubal A. Early, hoping it would force Grant to

disengage forces to pursue him. Early

invaded north through the Shenandoah Valley and reached the outskirts of Washington, D.C. Although unable to take the city, Early embarrassed the

Administration simply by threatening its inhabitants, making Abraham Lincoln's

re-election prospects even bleaker.

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, portrait by Mathew

Brady

In early

September, the efforts of Grant's coordinated strategy finally bore fruit. First, Sherman took Atlanta. Then, Grant dispatched Philip Sheridan to the Shenandoah Valley

to deal with Early. It became clear to

the people of the North that the war was being won, and Lincoln was re-elected

by a wide margin. Later in November,

Sherman began his March to the Sea. Sheridan and Sherman both followed Grant's

strategy of total war by destroying the economic

infrastructures of the Valley and a large swath of Georgia and the Carolinas.

At the

beginning of April 1865, Grant's relentless pressure finally forced Lee to

evacuate Richmond, and after a nine-day retreat, Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House

on April 9, 1865. There, Grant offered generous terms that did

much to ease the tensions between the armies and preserve some semblance of

Southern pride, which would be needed to reconcile the warring sides. Within a few weeks, the American Civil War

was effectively over; minor actions would continue until Kirby Smith surrendered his forces in the Trans-Mississippi

Department on June 2, 1865.

Immediately

after Lee's surrender, Grant had the sad honor of serving as a pallbearer at

the funeral of his greatest champion, Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln had been quoted after the massive

losses at Shiloh, "I can't spare this general. He fights." It was a two-sentence description that

completely caught the essence of Ulysses S. Grant.

Grant's

fighting style was what one fellow general called "that of a

bulldog." The term accurately

captures his tenacity, but it oversimplifies his considerable strategic and

tactical capabilities. Although a

master of combat by out-maneuvering his opponent (such as at Vicksburg and in

the Overland Campaign against Lee), Grant was not afraid to order direct

assaults, often when the Confederates were themselves launching offensives

against him. Such tactics often resulted

in heavy casualties for Grant's men, but they wore down the Confederate forces

proportionately more and inflicted irreplaceable losses. Copperheads denounced Grant as a "butcher"

in 1864, but they wanted the Confederacy to win. Although Grant lost battles in 1864, he won all his campaigns.

After

the war, on July 25, 1866,

Congress authorized the newly created rank of General

of the Army of the United States, the equivalent of a full

(four-star) general in the modern U.S. Army. Grant was appointed as such by President Andrew Johnson on the same day.

Grant and Johnson: As commander in chief of the army, Grant had a difficult

relationship with President Johnson. He

accompanied Johnson on a national stumping tour during the 1866 elections but

did not appear to be a supporter of Johnson's moderate policies toward the

South. Johnson tried to use Grant to

defeat the Radical Republicans by making Grant the Secretary of War in place of

Edwin M. Stanton, whom he could not remove

without the approval of Congress under the Tenure of Office Act. Grant refused but kept his military command.

That made him a hero to the Radicals, who gave him the Republican

nomination for president in 1868. He

was chosen as the Republican

presidential candidate at the Republican

National Convention in Chicago in May 1868, with no real

opposition. In his letter of acceptance

to the party, Grant concluded with "Let us have peace," which became

the Republican campaign slogan. In the general

election that year, he won against former New York governor Horatio Seymour with a lead of 300,000 out of a

total of 5,716,082 votes cast but by a commanding 214 Electoral College votes

to 80. He ran about 100,000 votes ahead

of the Republican ticket, suggesting an unusually powerful appeal to

veterans. When he entered the White

House, he was politically inexperienced and, at age 46, the youngest man yet

elected president.

Presidency 1869–1877

Grant

was the 18th President of the United States and served two terms from March 4, 1869,

to March 4, 1877. In the

1872 election he won by a landslide against the breakaway

Liberal Republican party that nominated Horace Greeley.

18th President of

the United States

|

Ulysses S.

Grant |

|

|

In office |

|

|

Vice President(s) |

Schuyler Colfax (1869-1873), |

|

Preceded by |

|

|

Succeeded by |

|

|

Born |

|

|

Died |

|

|

Political party |

|

|

Spouse |

|

|

Religion |

Never

baptized |

|

Signature |

|

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant, April 27, 1822

– July 23, 1885)

was an American soldier and

politician who was elected the 18th President of

the United States (1869–1877).

He achieved international fame as the leading Union

general in the American Civil War.

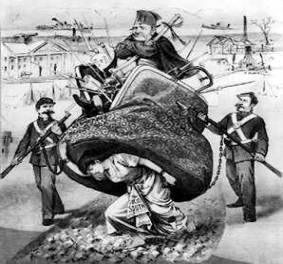

Critical

cartoonist ridicules imperial inauguration of Grant in 1869, compared to

Jeffersonian simplicity (upper left).

Policies: Grant presided over the

last half of Reconstruction,

watching as the Democrats (called Redeemers) took control of every state away from

his Republican coalition. When urgent

telegrams from state leaders begged for help, Grant and his attorney general

replied that "the whole public is tired of these annual autumnal outbreaks

in the South," saying that state militias should handle the problems, not

the Army. He supported amnesty for

Confederate leaders and protection for the civil rights of African-Americans.

He

favored a limited number of troops to be stationed in the South—sufficient

numbers to protect rights of southern blacks, suppress the violent tactics of

the Ku Klux Klan, and prop up Republican governors,

but not so many as to create resentment in the general population. In 1869 and 1871, Grant signed bills

promoting voting rights and

prosecuting Klan leaders. The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution,

establishing voting rights, was ratified in 1870. Recent scholarly work has begun to argue for the significance of

Ulysses S. Grant on the development of Reconstruction. Not only have these scholars provided

evidence for Grant's commitment to protecting Unionists and freedmen in the

South immediately after the Civil War, but have also argued for Grant's support

of intervention in the South right up until the election of 1876. Grant's

commitment to black civil rights can be easily seen by his address to Congress

in 1875 and by his attempt to use the annexation of Santo Domingo

as leverage to force white supremacists to accept blacks as part of the

southern political polity.

Grant

confronted an apathetic Northern public, violent terrorist organizations in the

South, and a factional Republican party.

Grant was charged with bringing order and equality to the South without

being armed with the emergency powers that Lincoln and Johnson employed. Given the formidable task it can be argued

that Grant did as much as could be done.

Grant

signed a bill into law that created Yellowstone

National Park (America's first National Park) on March 1, 1872.

The Panic of 1873 hit the country hard during his

presidency, and he never attempted decisive action one way or the other to

alleviate distress. The first law that

he signed, in March 1869, established the value of the greenback currency

issued during the Civil War, pledging to redeem the bills in gold. In 1874, he vetoed a bill to increase the

amount of a legal tender currency, which defused the currency crisis on Wall

Street but did little to help the economy as a whole. The depression led to Democratic victories in the 1874 off-year

elections, as that party took control of the House for the first time since

1856.

In

foreign affairs, a notable achievement of the Grant administration was the 1871

Treaty of Washington,

negotiated by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish.

It settled American claims against Britain concerning the wartime

activities of the British-built Confederate raider CSS Alabama. He proposed to annex the independent, largely black nation of Santo Domingo. Not only did he believe that the island

would be of use to the navy tactically, but he sought to use it as a bargaining

chip. By providing a safe haven for the

freedmen, Grant believed that the exodus of black labor would force Southern

whites to realize the necessity of such a significant workforce and accept

their civil rights.

At the

same time he hoped that U.S. ownership of the island would urge nearby Cuba and

Haiti to abandon slavery. The Senate

refused to ratify it because of (Foreign

Relations Committee Chairman) Senator Charles Sumner's strong opposition. Grant helped depose Sumner from the

chairmanship, and Sumner supported Horace Greeley and the Liberal

Republicans in 1872.

In 1876, Grant helped to calm the nation over the Hayes-Tilden election

controversy. He made it

clear he would not tolerate any march on Washington, such as that proposed by

Tilden supporter Henry Watterson.

Reconstruction

Policy

Culver Pictures

Cartoon of

the Carpetbaggers: This cartoon is critical of the so-called

carpetbaggers, government agents and others from the North who often took

advantage of the South after the American Civil War ended in 1865. It was published to ridicule the

administration of United States President Ulysses S. Grant. Culver Pictures

A

great variety of complex internal problems confronted the nation when Grant

took office in March 1869. Paramount

among these was the Reconstruction of the South and the reestablishment of

relations between the seceded states and the federal government.

Grant

dealt ineptly with Reconstruction.

After a visit to the South in 1865 he had made a report to President

Johnson supporting Johnson's moderation policy. His letter of acceptance to the Republican convention had

exhorted: “Let us have peace.” In his

first months as president, Grant listened to the counsel of moderation. He smoothed the road to congressional

legislation that would speed the readmission of Virginia, Mississippi, and

Texas to the Union. The other Southern

states had been readmitted earlier.

By

1870, however, most of the moderate Republicans had shifted their views toward

those held by the Radicals. It was

clear that Reconstruction was not working as intended. Although the new

governments of the South, elected by blacks and Unionist whites, had ended

restrictions against blacks and extended social services, most white

Southerners refused to accept the changes.

Violent organizations like the Ku Klux Klan began to terrorize black

leaders and keep black voters away from the polls to ensure the election of

their own candidates.

Grant

approved the punitive Force Acts of 1870 and 1871 to curb the violence. It was made a federal crime to interfere

with civil rights, and the president was authorized to declare martial law

(government by the military) where there was severe disorder. Grant did so only once, in nine counties of

South Carolina, and managed to break the Klan's grip on that state. There was little more he could do, however,

because the army was very small, and the North was too exhausted by the Civil

War to be willing to build it up again.

By 1876 most blacks had been driven from the polls, and the

white-elected governments were free to start their program of segregation, or

separation of the races. Segregation prevented most blacks in the South from

having economic or political power for the next 70 years.

Monetary

Policy: Grant's administration also faced financial

problems. Farmers and laborers, who

were often debtors, wanted to keep the paper money called greenbacks in

circulation. Greenbacks, which had been

issued to finance the Civil War, were soft money. There was no reserve of gold kept in the Treasury to guarantee

payment if a holder wanted to turn them in for coin. Thus they varied in value in relation to gold, and a $1 greenback

was usually worth less than a dollar gold piece. At one point it took $2.85 in greenbacks to buy a $1 gold

piece. The government also authorized

the issuance of national bank notes, which were backed by government bonds and

thus did not vary in value. They were

called hard money. Creditors did not

want to be repaid in money that was not worth its face value, but to debtors

this was an advantage.

The

Democratic Party appealed to debtors in the 1868 campaign by promising to keep

the greenbacks in circulation to pay off the government bonds issued during the

war. The Republicans believed in hard

money, and Grant held firmly to this position.

In his inaugural address in 1869, he insisted that the war bond debt be

paid in gold. Later that year he signed

the Public Credit Act, pledging payment in gold or coin to holders of

government bonds. However, Grant knew

little about finance and was inconsistent in his monetary policy. He did nothing about the greenbacks, and

they remained a threat to fiscal stability.

The U.S. Treasury had to intervene frequently in the money market, by

buying or selling gold or federal securities, because every serious political

change or international disturbance threatened to destroy the delicate balance between

greenbacks and gold.

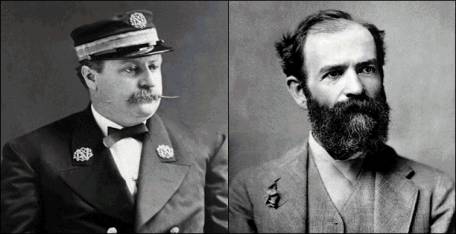

Black

Friday

Culver Pictures

The

Manipulators of Black Friday, Jim Fisk, above left, and Jay Gould, were two of

the most notorious financial speculators in the era of freewheeling capitalism

called the Gilded Age. In 1869 they

embarrassed the administration of United States President Ulysses S. Grant with

their scheme to corner the market in gold.

They bid up the price of gold on "Black Friday," September 24,

1869, ruining many investors. The

president acted quickly to restore the price to normal, but was widely blamed

for allowing the panic to occur.

In

the first year of Grant's presidency, the constant variation in the value of

greenbacks against the gold dollar enabled two speculators, Jay Gould and James

Fisk, to create a major financial crisis.

They set out to corner the market for gold by buying a significant part

of the gold offered for sale on the New York City Gold Exchange, where most

gold in the country was bought and sold.

The government could foil their scheme by putting its gold reserves on

the market, but Gould and Fisk spread the rumor that the president had agreed

not to do so.

Fisk

and Gould then bought gold on the New York exchange until, in a few days, the

price shot up by 20 percent. Many

businessmen who were locked into contracts to buy gold with greenbacks—which

had not increased in value—were ruined.

Prices of many commodities became unstable; foreign trade, which was

conducted in gold, was paralyzed; and the stock market came to a halt on the

day known as Black Friday, September 24, 1869.

Grant and his able secretary of the treasury, George S. Boutwell, who had

replaced Stewart, narrowly saved the market from collapse by releasing $4

million in government gold for sale before the end of the trading day.

This

action broke the corner; but then the gold price sank even faster than it had

risen, ruining other businessmen who had invested in the rising market. Economic activity was depressed for weeks

afterward. The president and Boutwell

were widely blamed for the economic crisis, even though they had not known of

the scheme, had acted promptly to stop it, and had fired all government

officials involved.

E-Foreign

Policy: Only in the conduct of foreign affairs,

where Grant largely followed the advice of Hamilton Fish, was his

administration at all remarkable. The

long controversy with Britain over payment for damages inflicted during the

Civil War by the Alabama and other British-built Confederate ships was

submitted for international arbitration in 1871. Its settlement the following year greatly strengthened the relationship

between the United States and Britain.

Scandals: The first scandal to taint the Grant

administration was Black Friday,

a gold-speculation financial crisis in September 1869, set up by Wall Street

manipulators Jay Gould and James Fisk. They tried to corner the gold market and tricked

Grant into preventing his treasury secretary from stopping the fraud. Several

of Grant's aides were suspected of inside dealings, but the president himself

had been totally fooled.

The most

famous scandal was the Whiskey Ring of 1875,

exposed by Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin H. Bristow,

in which over $3 million in taxes was stolen from the federal government with

the aid of high government officials. Orville E. Babcock,

the private secretary to the President, was indicted as a member of the ring but

escaped conviction because of a presidential pardon. Grant's earlier statement,

"Let no guilty man escape" rang hollow. Secretary of War William W. Belknap

was discovered to have taken bribes in exchange for the sale of Native

American trading posts. Grant's acceptance of the resignation of

Belknap allowed Belknap, after he was impeached by Congress for his actions, to

escape conviction, since he was no longer a government official. Other scandals included the Sanborn Incident at the Treasury and problems

with U.S. Attorney Cyrus I. Scofield.

Although Grant himself did not profit from corruption among his

subordinates, he did not take a firm stance against malefactors and failed to

react strongly even after their guilt was established. When critics complained, he vigorously

attacked them. He was weak in his selection of subordinates, favoring

colleagues from the war over those with more practical political experience. He alienated party leaders by giving many

posts to his friends and political contributors rather than supporting the

party's needs. His failure to establish

working political alliances in Congress allowed the scandals to spin out of

control. At the conclusion of his

second term, Grant wrote to Congress that "Failures have been errors of

judgment, not of intent."

Anti-Semitism Grant's legacy has been marred by anti-Semitism. The most frequently cited example

is the infamous General Order No.

11, issued by Grant's headquarters in Oxford, Mississippi,

on December 17, 1862,

during the early Vicksburg Campaign.

The order stated in part:

“The Jews, as a class, violating every regulation of trade established by

the Treasury Department, and also Department orders, are hereby expelled from

the Department (comprising areas of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky).”

The

order was almost immediately rescinded by President Lincoln. Grant maintained that he was unaware that a

staff officer issued it in his name.

Grant's father Jesse Grant was involved; General James H. Wilson later explained, "There was

a mean nasty streak in old Jesse Grant.

He was close and greedy. He came

down into Tennessee with a Jew trader that he wanted his son to help, and with

whom he was going to share the profits. Grant refused to issue a permit and

sent the Jew flying, prohibiting Jews from entering the line."

Grant,

Wilson felt, could not strike back directly at the "lot of relatives who

were always trying to use him" and perhaps struck instead at what he

maliciously saw as their counterpart—opportunistic traders who were

Jewish. Although it was portrayed as

being outside the normal inclinations and character of Grant, it has been

suggested by Bertram Korn that the

order was part of a consistent pattern.

"This was not the first discriminatory order [Grant] had signed...

he was firmly convinced of the Jews' guilt and was eager to use any means of

ridding himself of them."

The issue of anti-Semitism was raised during the 1868 presidential

campaign, and Grant consulted with several Jewish community leaders,

all of whom said they were convinced that Order 11 was an anomaly, and he was

not an anti-Semite. He maintained good

relations with the community throughout his administration, on both political

and social levels.

Administration and Cabinet

Grant

Memorial Statue in Grant Park, Galena, Illinois. Julia Grant remarked that it was the best likeness of her

husband, as his hands were thrust into his pockets. The following is a summary of the Cabinet Members of the Grant

Administration:

|

OFFICE |

NAME |

TERM |

|

Ulysses S. Grant |

1869–1877 |

|

|

1869–1873 |

||

|

|

1873–1875 |

|

|

1869 |

||

|

|

1869–1877 |

|

|

1869–1873 |

||

|

|

1873–1874 |

|

|

|

1874–1876 |

|

|

|

1876–1877 |

|

|

1869 |

||

|

|

1869 |

|

|

|

1869–1876 |

|

|

|

1876 |

|

|

|

1876–1877 |

|

|

1869–1870 |

||

|

|

1870–1871 |

|

|

|

1871–1875 |

|

|

|

1875–1876 |

|

|

|

1876–1877 |

|

|

1869–1874 |

||

|

|

1874 |

|

|

|

1874–1876 |

|

|

|

1876–1877 |

|

|

1869 |

||

|

|

1869–1877 |

|

|

1869–1870 |

||

|

|

1870–1875 |

|

|

|

1875–1877 |

Supreme

Court Appointments: Grant appointed the

following Justices to the Supreme

Court of the United States:

- William Strong

– 1870

- Joseph P. Bradley

– 1870

- Ward Hunt – 1873

- Morrison Remick

Waite (Chief

Justice) – 1874

States Admitted to the Union:

Government Agencies Instituted:

- Department

of Justice (1870)

- Office of the Solicitor

General (1870)

- Post Office

Department (1872)

- "Advisory Board on Civil Service" (1871); after it expired

in 1873, it became the role model for the "Civil Service

Commission" instituted in 1883 by President Chester A. Arthur,

a Grant faithful. (Today it is known as the Office of

Personnel Management.)

- Office of the Surgeon

General (1871)

- Army Weather Bureau (currently known as the National

Weather Service) (1870)

Election

of 1872: Toward the end of his first administration,

Grant's Southern policy, coupled with public scandals involving his political

advisers and appointees, led to widespread public disapproval. The Congressional and state elections of

1870 resulted in a setback for Grant's administration. By 1872 a formidable reformist wave was

beginning to roll across the nation.

The Republicans nominated Grant for reelection, but a new, anti-Grant

Liberal Republican Party combined with the Democrats to nominate Horace

Greeley, publisher of the New York Tribune, to run against him.

Although

Grant was assailed for his mal-administration in both the Liberal Republican

and Democratic platforms, he was overwhelmingly reelected. He carried every Northern state and most of

the South, receiving 3,596,745 votes to Greeley's 2,843,446. Greeley died less than one month after the

election, and when the electors met they spread his electoral votes among

several other candidates. The final

vote of the electors was Grant, 286; Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana, 42;

Benjamin Gratz Brown of Missouri, 18; Charles J. Jenkins of Georgia, 2; David

Davis of Illinois, 1. Seventeen electors did not vote.

Grant

had made an even better showing in reelection than in 1868. This was important to him. He had not cared intensely about his first

election, but about 1872, he later said, “My reelection was a great

gratification because it showed me how the country felt.”

Second

Term Administration: Grant's second

administration was even less successful than the first. A series of scandals in government was

unearthed. Although Grant was

implicated in none of them, the improprieties committed by officials in his

government and by members of his party in Congress reflected on the

president. His continued loyalty to

friends whose abuse of public office was well known did not add to Grant's

prestige.

A congressional investigation of the Crédit Mobilier

swindle, involving stockholders in the Union Pacific Railroad, was completed in

1873. It was found that the Crédit

Mobilier company, formed to do the Union Pacific's construction work, had

overcharged millions of dollars on government contracts. Furthermore, one of its principal

stockholders, Congressman Oakes Ames of Massachusetts, had tried to buy off the

investigation by distributing stock among his colleagues. Those implicated in the scandal included Vice

President Colfax and several Republican senators and representatives, including

a future president of the United States, James A. Garfield (1881).

Also in 1873, Grant's secretary of the treasury, William

A. Richardson, came under fire for an irregular tax collection scheme, known as

the Sanborn Contracts. In May 1874 the

House Ways and Means Committee declared that Richardson deserved “severe

condemnation.” The committee privately

urged Grant to remove Richardson. The

president complied but made Richardson a U.S. Court of Claims judge.

Richardson's successor, Benjamin H. Bristow, broke up

the notorious Whiskey Ring, a conspiracy among Internal Revenue Service

officials to defraud the government of liquor taxes. Among the more than 200 people involved was Orville E. Babcock,

Grant's private secretary and formerly his aide-de-camp during the Civil

War. When Babcock was indicted in

December 1875 for conspiracy to defraud the revenue, Grant volunteered a

deposition that he knew of nothing suggesting Babcock's guilt and that Babcock

was innocent. Grant's intercession

saved Babcock from conviction and allowed him to resume his secretarial duties

for a time.

Discoveries of other frauds in the U.S. Treasury and in

the Indian Service came to light as Grant's second administration drew to a

close. However, the president remained

loyal to his friends, almost regardless of what their conduct had been or of

how seriously they had damaged his reputation.

Third Term Attempt in 1880: In 1879, the "Stalwart" faction of the Republican

Party led by Senator Roscoe Conkling

sought to nominate Grant for a third term as president. He counted on strong

support from the business men, the old soldiers, and the Methodist church. Publicly Grant said nothing,

but privately he wanted the job and encouraged his men. His popularity was

fading however, and while he received more than 300 votes in each of the 36

ballots of the 1880

convention, the nomination went to James A. Garfield. Grant campaigned for Garfield

for a month, but he supported Conkling in the terrific battle over patronage in

spring 1881 that culminated in Garfield's assassination

Last Years: Grant's followers planned to nominate him for

a third presidential term in 1876, but the leaders of the Republican National

Convention opposed his re-nomination. They named Governor Rutherford B. Hayes

of Ohio as the party's standard-bearer, and he won the election. Grant left office in March 1877, with a few

thousand dollars saved and a desire to see the world.

On May 17 he sailed with his family for

Liverpool, England, on the first leg of a journey around the world. Everywhere he was well received, not as the

former president of the United States, but as the hero of the Civil War. He met and talked with many foreign

leaders. John Russell Young's Around

the World With General Grant (1879) provides an account of some of Grant's

impressions and conversations. Grant's

last years were bitter ones.

He had given up an assured income for life when

he resigned from the army to become president. For a year after returning to the United

States, his family lived on the income from a $250,000 fund collected for him

by friends. When the securities in

which the fund was invested failed, Grant was once again without financial

resources.

Not

until 1885 did Congress vote to restore Grant's rank of full general with an

appropriate salary. By that time he was

fatally ill. He was moved to Mount

McGregor, near Saratoga, New York, in an effort to restore his health. There he began to write his recollections of

the war years, the Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant (1885-1886). They were completed only a week before he

died of cancer of the throat. Because

in the last months of his life he was unable to speak, the memoirs were in

large part written out in his own hand.

World Tour:

After the end of his second term in the White House, Grant spent two

years traveling around the world with his wife. He visited Ireland, Scotland, and England; the crowds were

huge. The Grants dined with Queen Victoria and Prince Bismarck in Germany. They also visited Russia, Egypt, the Holy

Land, Siam, and Burma. In Japan, they

were cordially received by Emperor Meiji and Empress Dowager Shoken

at the Imperial Palace. Today in the Shibakoen section of Tokyo,

a tree still stands that Grant planted during his stay.

In 1879, the Meiji government of Japan announced the

annexation of the Ryukyu Islands. China

objected, and Grant was asked to arbitrate the matter. He decided that Japan's claim to the islands

was stronger and ruled in Japan's favor.

After

two years of travel, Grant returned home.

He was still interested in a third term as president, but at the

convention in 1880 the nomination went to James A. Garfield. Grant's political

career was at an end.

Grant's Significant Acts for the two Terms in Office

General

Status:

Congress, although unofficially given to George Washington during the

American Revolution, first officially created the title of general, in the

United States in 1799. Washington,

Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Philip H. Sheridan, and John J. Pershing

were the only men to hold this rank permanently until World War II, when many

generals were appointed. The U.S. Army

and Air Force chiefs of staff hold this title by statutory designation, as do

several others holding high-ranking positions.

The insignia in the U.S. is four silver stars on each shoulder strap and

collar lapel. In December 1944, the

rank of General of the Army was created, with an insignia of five silver stars,

in order to make U.S. commanders equal to European field marshals. Omar N. Bradley, Dwight D. Eisenhower,

Douglas Macarthur, and George C. Marshall, as well as Henry H. Arnold of the

Air Force held this rank. Previously,

General of the Army had been an honorary rank, conferred only on Pershing after

World War I.

Forty

Acres and a Mule:

The Civil War ended in May 1865, and six months later President Andrew

Johnson sent General Ulysses S. Grant on an information-gathering tour of the

South. In his letter to the president

upon his return, Grant made two key observations. First, he concluded that the federal government needed to keep

troops in the South. Second, he concluded

that most Southern blacks mistakenly believed that the Freedmen's Bureau was

going to give them land.

Many

freedmen did indeed believe they would receive “40 acres and a mule,” as had

been proposed by radical members of Congress, but those promises were not

realized. Grant talks about the freedmen being unwilling to sign labor

contracts agreeing to work in the fields, and he cites this as an indication

they did not want to work. What Grant

does not mention, however, is that those labor contracts restricted freedmen to

conditions little better than slavery.

The contracts often forced the freedmen to work for their former

masters, but without the provisions for food and shelter that they had received

under the slave system. The language

reflects the conventions of the time in which the letter was written.

Stanton

Dismissal: Secretary of War

Stanton had been working with the Radicals from the beginning of Johnson’s

presidency. In August 1867, while

Congress was adjourned, Johnson suspended Stanton and named General Ulysses S.

Grant to the post. In January 1868 the

Senate refused to accept Stanton’s suspension.

When Grant stepped out in favor of Stanton, the president again

dismissed Stanton and appointed General Lorenzo Thomas as secretary of

war. Supported by the Radicals, Stanton

barricaded himself in his War Department office and refused to let Thomas in.

Stock

Market: Saved

the stock market from collapse in September 1869 by allowing the sale of $4

million in government gold.

Military

Commission: After

the war the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Ex parte Milligan that

military tribunals could not properly try civilians where civil courts were

available. In 1871 Milligan sued the

military commission for $100,000 in damages.

Harrison was appointed special assistant U.S. attorney by the

administration of Ulysses S. Grant to defend the commission. Harrison argued that the military commission

had acted in good faith. The jury,

aware that the law was on Milligan's side, had no alternative but to declare in

his favor; Harrison's victory lay in the damages awarded to Milligan—a mere $5.

William

Howard Taft Served Under President Grant: Taft was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the son

of Alphonso and Louisa Torrey Taft.

Both parents were descendants of old and substantial New England

families of British origin. His father,

a native of Vermont and the son of a judge, had moved to Cincinnati in 1837 to

practice law. His mother came to Ohio

from Massachusetts years later as Alphonso's second wife. Their first son died in infancy, but in

1857, William Howard Taft was born, healthy and strong. In time there were six children, including

William, his two brothers, his sister, and his two half brothers by his

father's first marriage.

Traditions

revering education and public service ran strong in the family. Alphonso Taft himself served as a judge in

Ohio, as attorney general and secretary of war in the administration of Ulysses

S. Grant (1869-1877), and as U.S. minister to Austria and to Russia. He set an example that his son William was

to emulate and exceed.

First

Black Diplomat

In

1869 President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Bassett U.S. minister to Haiti and

the Dominican Republic, giving the United States its first black diplomat. Letters on file in the National Archives

urging Bassett's appointment came from many prominent citizens, including 12 of

his Yale professors.

He

signed the Force Acts of 1870 and 1871 to ensure the voting rights of blacks by

making it a crime to interfere with civil rights.

Endangered

Species Act:

The U.S.

government’s interest in preserving species in danger of extinction can be

traced back to the 19th century. In an

effort to curtail the mass destruction of the nation's bison population,

Congress passed the Buffalo Protection Act in 1875 to safeguard the relatively

few remaining bison. However, President

Ulysses S. Grant vetoed the act. For

nearly a century thereafter no legislation that directly addressed the issue of

endangered species was signed into law.

Yellowstone

National Park: Slightly

more than 125 years ago, on March 1, 1872, United States President Ulysses S.

Grant signed a bill creating Yellowstone National Park. Carved primarily out of what was then the

Wyoming Territory, Yellowstone became the nation's (and the world's) first

national park, set aside for the “benefit and enjoyment of the people,”

according to the text of the bill.

Since that time, Yellowstone has served as a model for parks and

preserves throughout the United States and around the world.

Over

the course of its 125-year history, the park has served many purposes: national

symbol, natural laboratory for scientists and naturalists, and a place where

visitors may glimpse an earlier, wilder America. Abounding in natural splendor, Yellowstone is perhaps most famous

for its geysers, steam vents, and hot springs.

The park is also home to a wide variety of wildlife, including elk,

bison, and grizzly bears. It is also an

ongoing experiment in the dynamic and challenging relationship between human

beings and nature.

KKK Proclamation: Attired in sheets and wearing masks with

pointed hoods, Klansmen terrorized public officials and blacks. From 1868 to 1870, while federal occupation

troops were being withdrawn from the southern states and radical regimes

replaced with Democratic administrations, the Klan was increasingly dominated

by the rougher elements in the population.

The local organizations, called klaverns, became so uncontrollable and

violent that the Grand Wizard, former Confederate general Nathan B. Forrest,

officially disbanded the Klan in 1869. Klaverns,

however, continued to operate on their own.

In 1871, Congress passed

the Force Bill to implement the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

guaranteeing the rights of all citizens.

In the same year President Ulysses S. Grant issued a proclamation

calling on members of illegal organizations to disarm and disband; thereafter

hundreds of

Klansmen were arrested. The remaining

klaverns gradually faded as the political and social subordination of blacks

was reestablished.

President

Johnson Impeachment and 15th Amendment: By 1869 the Republican Party was firmly in

control of all three branches of the federal government. After attempting to remove Secretary of War

Edwin M. Stanton, in apparent violation of the new Tenure of Office Act,

Johnson had been impeached by the House of Representatives in 1868. Although the Senate, by a single vote,

failed to convict him, his power to obstruct the course of Reconstruction was

gone. Republican Ulysses S. Grant was

elected president that fall. Soon

afterward, Congress approved the 15th Amendment, prohibiting states from

restricting the franchise because of race.

Then it enacted a series of Enforcement Acts authorizing national action

to suppress political violence. In 1871

the administration launched a legal and military offensive that destroyed the

Klan. Grant was reelected in 1872 in

the most peaceful election of the period.

Martial

Law in South Carolina:

Hundreds of blacks were killed for attempting to vote, for challenging

segregation and for organizing workers.

To regain power in state governments, Southern Democrats used violence

to keep black voters away from the polls.

Throughout Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist

groups conducted terrorist attacks on African Americans and their allies to

limit Republican political power and restrict black opportunities. Hundreds of blacks were killed for

attempting to vote, for challenging segregation, for organizing workers, or

even for attending school.

In

1871 President Ulysses S. Grant declared martial law in nine South Carolina

counties because of the proliferation of lynching and beatings. In 1873 white terrorists massacred more than

60 blacks on Easter Sunday in Colfax, Louisiana and killed 60 Republicans, both

blacks and whites, during the summer of 1874 in nearby Coushatta. They killed 75 Republicans in Vicksburg,

Mississippi in December 1874.

Settled

claims against Britain in 1872 for damage done during the Civil War by

British-built Confederate warships.

Buffalo

Pocket Veto: If you

dine on buffalo, history makes a bitter sauce.

The indiscriminate slaughter of millions of animals on the frontier

provoked outrage in Congress, which in 1874 voted overwhelmingly to end it in

the federally controlled territories.

The bill was pocket vetoed by President Ulysses S. Grant, whose army was

losing as many as 25 troopers for every Indian killed in a campaign to confine

them to reservations.

Arkansas

Corruption Charges:

There was some corruption in the state Republican Party, however, and it

culminated in what was known as the Brooks-Baxter War. Elisha Baxter, a Republican, won the 1872

election for governor; his opponent, Joseph Brooks, also a Republican, charged

fraud. In early 1874 armed forces of

the two rivals clashed on Main Street in Little Rock. Other clashes occurred elsewhere around the state, and about 200

people were killed. President Ulysses S. Grant eventually declared that Baxter

was the governor.

Secretary

of War Impeachment:

The United States Senate has held full impeachment trials 14 other times

in American history. Twelve federal

judges have been tried, and seven were convicted. The Senate acquitted four judges, and one resigned before the

trial was complete. The Senate also

tried and acquitted William W. Belknap, secretary of war during the

administration of President Ulysses S. Grant.

Wyoming

Territory: Hence,

Dakota laws were enforced in Wyoming until the following year when President

Ulysses S. Grant took office and the Congress approved his territorial

appointments. John A. Campbell was

named the first territorial governor, and Cheyenne became Wyoming Territory’s

temporary capital.

World

Events 1861-1865:

Date Event

1861 The

Civil War between the United States of America and the Confederate States of

America begins.

The Kingdom of Italy is proclaimed with Victor

Emmanuel II as king and Camillo Benso, Conte di Cavour as prime minister.

Czar Alexander II abolishes 1861 Serfdom in

Russia.

1862

An income tax is levied in the United

States to help pay for war costs.

The United States homestead law encourages

settlement in the West by allowing those who qualify to acquire homesteads.

1863 President

Abraham Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation, proclaiming freedom for

all slaves in Confederate-held territory.

1865 Confederate

General Robert E. Lee surrenders to U.S. General Ulysses S. Grant, ending the

American Civil War.

Bankruptcy: In

1881, Grant purchased a house in New York City and placed almost all of his

financial assets into an investment banking partnership with Ferdinand Ward, as

suggested by Grant's son Buck (Ulysses, Jr.), who was having success on Wall Street. Ward swindled Grant (and other

investors who had been encouraged by Grant) in 1884, bankrupted the company, Grant and Ward, and

fled.

Memoirs:

Grant learned at the same time that he was suffering from

throat cancer. Grant and his family were left

destitute; at the time retired U.S. Presidents were not given pensions, and Grant had forfeited his military pension

when he assumed the office of President.

Grant first wrote several articles on his Civil War campaigns for The Century Magazine,

which were warmly received.

Mark Twain offered

Grant a generous contract, including 75% of the book's sales as royalties. The book was a resounding success. Grant focused on the Civil War, the period

of his greatest glory, yet he did not write to glorify or justify himself. He attempted to tell what really happened,

admitting his mistakes and sharing credit with others. His book remains one of the Great War

commentaries of all time.

Terminally

ill, Grant finished the book just a few days before his death. The memoirs

sold over 300,000 copies, earning the Grant family over $450,000. Twain hyped the book as "the most

remarkable work of its kind since the Commentaries of Julius Caesar," and they are widely

regarded as among the finest memoirs ever written.

Just

before his death, Grant summed up his career in a note to his doctor: “It seems

that man's destiny in this world is quite as much a mystery as it is likely to

be in the next. I never thought of

acquiring rank in the profession I was educated for; yet it came with two

grades higher prefixed to the rank of General officer for me. I certainly never had either ambition or

taste for political life; yet I was twice President of the United States. If anyone ... suggested the idea of my

becoming an author ... I was not sure whether they were making sport of me or

not. I have now written a book which is in the hands of the manufacturers.”

Ulysses S. Grant died at 8:06 a.m. on

Thursday, July 23, 1885,

at the age of 63 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga County,

New York. His body lies in New York City's Riverside Park,

beside that of his wife, in Grant's Tomb, overlooking the Hudson River in New York

City, the largest mausoleum in North America.

In memoriam

Grant as

he appears on the 2004 series U.S. $50 note

- In World War II,

the British Army

produced an armored vehicle known as the Grant tank (a version of the American M3

model, which was ironically nicknamed the "Lee").

- Grant's portrait appears on the U.S. fifty-dollar

bill.

- The Ulysses S.

Grant Memorial, located on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C.,

honors Grant.

- Grant Park

in Chicago, Illinois

honors Grant.

- There is a U.S. Grant Bridge

over the Ohio River at Portsmouth, Ohio.

- There is a U.S.

Grant Memorial Highway (US 52) in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Counties

in ten U.S. states are named after Grant: Arkansas, Kansas, Minnesota,

Nebraska, New Mexico,

North Dakota,

Oklahoma, Washington,

West Virginia,

and Wisconsin

and Grant Parish,

Louisiana.

Grant Trivia:

- Grant was a descendant of Mayflower passenger Richard Warren.

- Grant was known to visit the Willard Hotel to escape the stress of the

White House. He referred to the

people who approached him in the lobby as "those damn

lobbyists," possibly giving rise to the modern term lobbyist.

- Grant's nicknames included: The Hero of Appomattox, "Unconditional

Surrender" Grant ("U.S. Grant"), Sam Grant,

and, in his youth, Ulys, Lyss and Useless.

- While in California, Grant tried selling ice to South America but failed when it melted in

the warm weather aboard the ship.

- The question "Who's buried in Grant's Tomb?" was used by Groucho Marx in his radio and TV quiz

show, the correct answer to which resulted in a consolation

prize to contestants who had won no money. Some contestants thought it was a trick question. Grant's grandson, Ulysses S. Grant IV